Friday, 20 February 2026

Why Cato believes reforms from the Republican Study Committee stop short of true fiscal reform

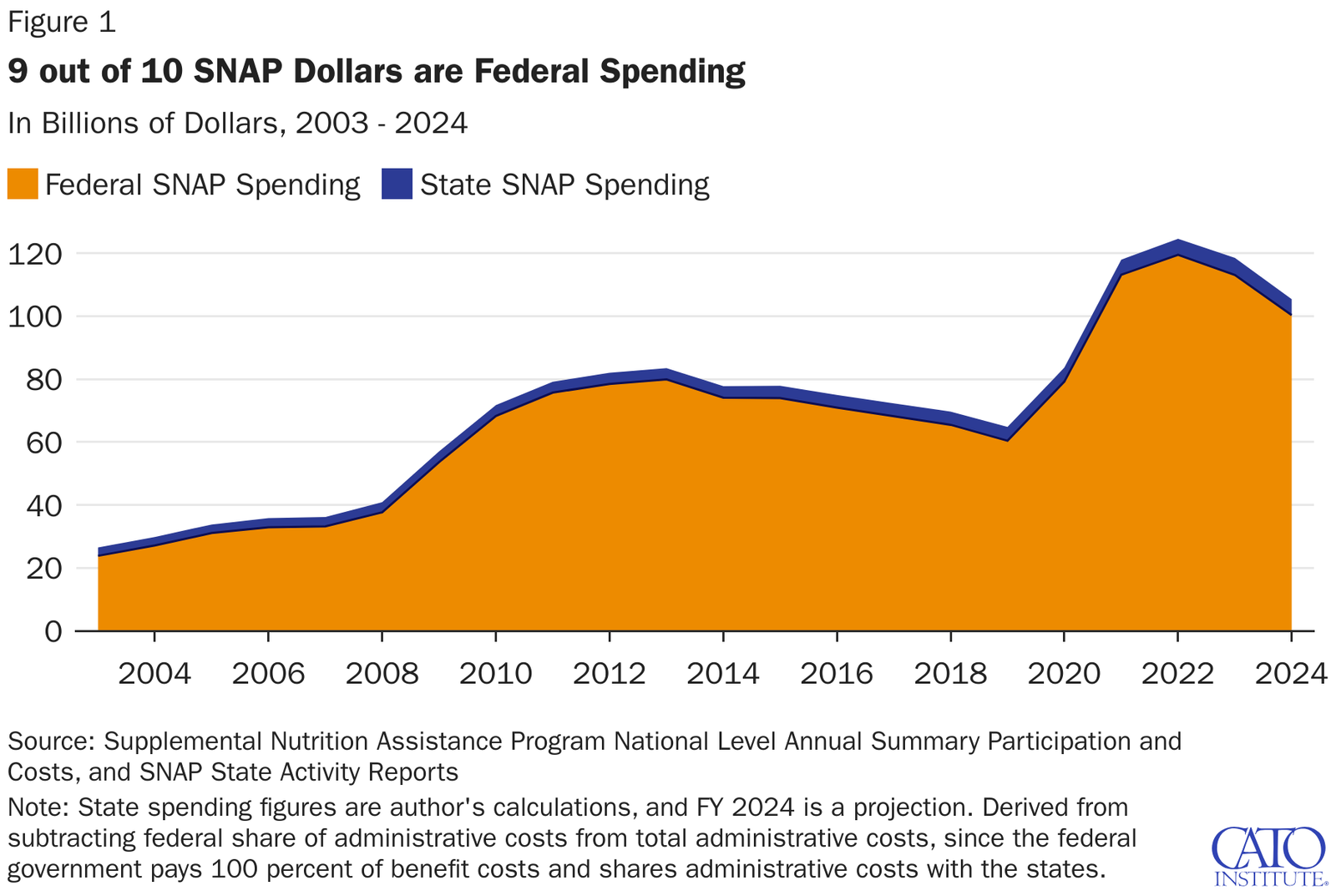

The Republican Study Committee has advanced a slate of SNAP reforms—tightening eligibility, eliminating broad-based categorical eligibility, barring noncitizens, strengthening quality controls, and expanding interstate data matching—to curb waste and rein in federal spending. While these measures promise meaningful savings, they largely refine compliance mechanisms without confronting the program’s deeper structural imbalance: states administer benefits that federal taxpayers overwhelmingly finance.

This misalignment of authority and fiscal responsibility, critics argue, perpetuates weak incentives to aggressively prevent fraud and control long-term cost growth. A more durable solution would realign funding with governance—through block grants or full devolution—placing accountability squarely with the entities that design and operate the program.

In an exclusive interview with AgroSpectrum, Romina Boccia, Director of Budget and Entitlement Policy at the Cato Institute, weighs in on the Republican Study Committee framework proposing tighter SNAP eligibility, elimination of broad-based categorical eligibility, stricter quality controls, and expanded data matching to curb waste. While she acknowledges these reforms could generate significant savings—potentially hundreds of billions over a decade—Romina argues they stop short of addressing SNAP’s core structural flaw: a federal–state financing model that divorces spending authority from fiscal responsibility.

The Republican Study Committee argues that tightening eligibility and verification will curb waste in SNAP. From Cato’s perspective, are these reforms meaningful structural fixes—or incremental guardrails around a fundamentally flawed program design?

The GOP’s SNAP reforms are a step in the right direction, but they only treat the symptoms of the problem. Tightening eligibility and verification may reduce improper payments at the margin, but it doesn’t fix SNAP’s core incentive problem. The federal government pays for benefits while states administer the program, meaning states have weak incentives to control costs. Structural reform would align program management with fiscal responsibility, whether through block grants or full devolution.

The RSC estimates that eliminating broad-based categorical eligibility could save $100 billion over 10 years. Do you view BBCE as a loophole that undermines statutory intent, or as a necessary flexibility tool for states managing poverty in high-cost regions?

Broad-based categorical eligibility allows states to bypass SNAP’s statutory income and asset limits, effectively expanding eligibility beyond what Congress intended. Because the federal government finances the benefits, states can broaden access without bearing the fiscal consequences. If states want greater discretion over eligibility, they should also assume greater financial responsibility.

A major pillar of the proposal would bar noncitizens from SNAP entirely. Does this approach meaningfully reduce long-term fiscal exposure, or does it risk unintended labor market and integration consequences that could increase state-level burdens?

Limiting noncitizen access to SNAP reduces federal spending. As an added political benefit, it reassures Americans that immigrants are coming to work—not to take advantage of American taxpayers. Building a wall around the welfare state, rather than around the country, can sustain public support for legal immigration that benefits Americans.

The framework introduces a zero-tolerance quality control threshold for payment errors. Is stricter auditing the right lever to pull—or does it risk penalizing administrative mistakes while failing to address deeper incentive misalignments?

Eliminating the QC threshold would increase program transparency by providing a more accurate measure of how much federal taxpayer money is lost to improper payments in SNAP and tighten enforcement. But stricter auditing alone doesn’t fix SNAP’s core incentive problem. As long as federal taxpayers finance benefits, states face limited fiscal consequences for errors. Greater accountability will come from aligning program authority with funding responsibilities.

You argue that states lack incentive to prevent improper payments because they do not finance SNAP benefits directly. Would converting SNAP into a block grant with state cost-sharing meaningfully reduce fraud—or simply shift fiscal risk during economic downturns?

Block-granting SNAP would give states a stronger incentive to reduce fraud, as they would no longer be able to rely on additional federal funding to finance benefit expansions or make up for improper payments resulting from lax oversight. Every dollar lost to waste would be a dollar unavailable for legitimate beneficiaries.

Under a block grant model, Congress could also allow states to carry over unspent funds and build reserves during economically strong periods—so-called rainy day funds—which they can draw from to help fund benefits during economic downturns, as is the case for the TANF block grant. However, as long as states are spending federal dollars—even with cost-sharing—some incentive distortions remain. Examples include states like California, which have resorted to using budget gimmicks to draw more federal dollars in Medicaid.

Ending federal financing of SNAP benefits altogether could save over $400 billion over a decade, according to your analysis. Politically and economically, is that a realistic path forward—or a theoretical benchmark to frame the debate?

The 1996 welfare reforms demonstrated both the political viability and positive outcomes of placing greater responsibility for anti-poverty programs on the states. Full devolution is the next step and builds on that precedent.

The Biden administration’s 2021 Thrifty Food Plan reevaluation increased SNAP benefits by more than 20 percent. Should Congress rescind that increase on constitutional or fiscal grounds—or would doing so risk destabilizing food security for low-income households?

Congress should rescind it on both constitutional and fiscal grounds. The Biden administration circumvented congressional spending authority and set a dangerous precedent for future unilateral executive benefit expansions. Rescinding the TFP expansion would also save taxpayers almost $300 billion over the next ten years—more than any of the SNAP-specific reforms proposed by the RSC.

If Congress implements tighter eligibility rules without reforming the federal–state financing structure, will fraud and improper payments materially decline—or will states simply find new administrative workarounds within the existing incentive framework?

It might reduce payment errors by catching them more quickly, but states will still have little reason to be proactive in combating fraud because any money wasted doesn’t come out of their own coffers. Moreover, stricter verification protocols risk incentivizing states to hide improper payments to avoid financial sanctions.

We saw this in 2015, when the USDA reported that 42 of 53 state SNAP agencies weakened their quality control processes to artificially lower reported payment errors. We still see this today, with states like California abusing discretionary waivers to cover up erroneously awarded benefits paid to able-bodied adults that do not meet the program’s work requirements.

— Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)