Friday, 27 February 2026

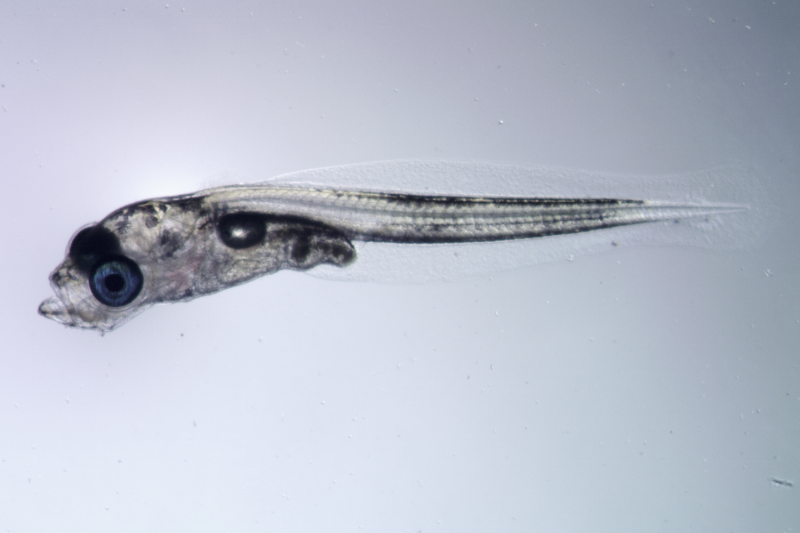

Image source: NOAA Fisheries / Emily Slesinger

Scientists trace climate impacts from ocean temperatures directly to larval gene activity

Rising ocean temperatures—not acidification alone—may be the critical factor behind recent declines in Pacific cod populations, according to a new gene expression study that sheds light on how changing ocean conditions affect the species at its most vulnerable life stage.

Researchers found that while newly hatched Pacific cod larvae possess genetic tools that allow them to tolerate cold and increasingly acidic waters, exposure to warming conditions can trigger fatal energy shortages and inflammatory responses. The findings suggest a direct biological link between marine heatwaves and reduced recruitment of Pacific cod in the Gulf of Alaska, one of the world’s most important commercial fisheries.

Pacific cod play a dual role in marine ecosystems as both predator and prey, while also supporting a highly valuable fishery. Yet stocks in Alaska have fallen sharply in recent years—a trend scientists increasingly associate with prolonged marine heatwaves. Early life stages appear especially vulnerable, raising concerns as climate-driven warming events become more frequent at high latitudes.

Why Heat Matters More Than Acidification

The study builds on controlled experiments conducted at NOAA Fisheries’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center, where Pacific cod were raised from embryos to larvae under different temperatures and acidity levels. Larvae exposed to warmer water experienced extremely high mortality, while the effects of ocean acidification were more nuanced and depended on developmental stage.

To understand why, scientists turned to gene expression analysis—examining which genes larvae activate under stress. “Rather than just observing survival outcomes, we wanted to understand the mechanisms driving mortality,” said Emily Slesinger, a researcher at NOAA Fisheries. “Gene expression allows us to see how larvae respond internally to environmental change.”

The molecular data revealed two dominant stress pathways under warming conditions: accelerated energy demand and heightened inflammation. As temperatures rise, larvae grow and develop faster, increasing metabolic needs. At the same time, immune and inflammatory responses are activated, which further drain limited energy reserves. When these demands exceed available fat stores and food intake, larvae can effectively starve.

A Complex Role for Acidification and Cold

By contrast, acidification alone did not appear to directly increase larval mortality. However, gene activity suggested it may interfere with fat absorption in the intestine, potentially weakening larvae in food-limited natural environments. Cold conditions triggered a different response: larvae increased production of enzymes and proteins to compensate for slower metabolism, though growth remained sluggish—potentially reducing survival to adulthood.

“Temperature has an outsized influence on gene activity in cold-blooded species like fish,” said Laura Spencer of the University of Washington, who led the molecular analysis. “Our results show that warming fundamentally reshapes larval physiology in ways that can be lethal.”

Implications for Fisheries and Climate Resilience

The study highlights how climate-driven warming may already be shaping the future of Pacific cod populations by disrupting survival at the earliest life stages. While some populations may carry genetic traits that confer resilience to specific conditions, warming emerged as the dominant threat.

“Overall, warming appears to be the main factor affecting cod larval physiology,” Spencer said. “That has serious implications for population recovery and long-term fishery sustainability.”

As marine heatwaves intensify and ocean chemistry continues to change, the findings underscore the importance of integrating molecular biology into fisheries management—linking climate trends not just to stock numbers, but to the biological processes that determine whether the next generation survives at all.