Friday, 27 February 2026

Caught between food diplomacy and brand dilution, basmati’s future depends on policy stability, traceability, and premium positioning

Few crops embody India’s agricultural heritage and global ambition like basmati rice. Long-grained and aromatic, basmati is both a cultural symbol and one of India’s most valuable agri-exports. Yet its future is increasingly uncertain. Policy volatility, geopolitical pressures, sustainability scrutiny, and intensifying competition—particularly from Pakistan—are forcing a strategic reckoning. The central question is no longer about scale, but positioning: should basmati be managed as a strategic commodity or elevated as a protected, premium global agri-brand ?

Few crops carry both heritage and ambition like Basmati rice. Long-grained, aromatic, and rooted in the Indo-Gangetic plains, it is more than food — it is a cultural symbol and a global premium brand. India dominates exports, but its future hinges on whether Basmati is treated as a strategic commodity or elevated as a premium agri-brand. “Basmati must be treated both as a strategic commodity and a premium agri-brand because it sits at the intersection of markets and geopolitics,” said Khushi Kesari, Program Officer at the History Lab, Advanced Study Institute of Asia. “Its premium value stems not only from where and how it is grown, but from the expectations global consumers associate with Indian basmati. At the same time, basmati is increasingly shaped by trade rules and political dynamics—visible in disputes with Pakistan, higher tariffs in the U.S., and tighter regulatory scrutiny in the EU.”

These forces directly affect market access, pricing, and farmer incomes. Kesari added: “Ultimately, how India strengthens enforcement and farm-to-export traceability will determine whether basmati continues to command global trust and premium value while advancing broader economic and diplomatic interests.”

Strategic Commodity vs. Premium Agri‑Brand

Few crops embody both heritage and economic ambition as vividly as Basmati rice. For India, the debate is no longer about whether Basmati is important—it is about how the nation chooses to treat it: as a tightly controlled strategic commodity or as a premium agri-brand capable of commanding global prestige.

“Basmati is far more than a rice variety—it is a strategic national asset for India,” argued Dev Garg, Vice President of the Indian Rice Exporters Federation (IREF). “Unlike generic varieties such as IR 64 or PR 106 that can be cultivated across diverse geographies, Basmati’s defining qualities—its aroma, grain elongation, texture, and colour—are inseparable from the unique soil, climate, and hydrological conditions of Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, and parts of Uttarakhand. This inimitable provenance cannot be replicated elsewhere, making Basmati not just a crop, but a globally distinctive product rooted in geography.”

“Basmati offers India a rare convergence of fiscal efficiency, farmer resilience, and global food influence. By shifting cultivation toward a premium, market-driven crop, the government can ease the MSP burden, improve farm incomes through private market access, and strengthen India’s leverage in global food diplomacy. Treating basmati as a premium commodity is not merely about price realisation—it is about advancing national interest through agriculture and trade.”

— Dev Garg, Vice President of the Indian Rice Exporters Federation (IREF)

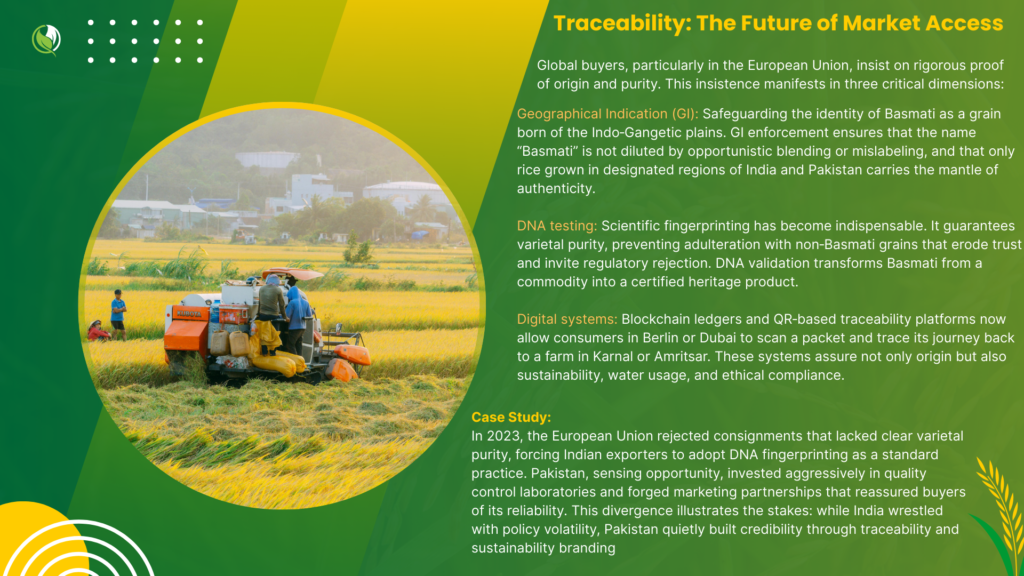

The global marketplace, meanwhile, is shifting toward transparency and proof-based trust. “From the EU’s mandatory PDO-PGI labels to Punjab’s basmati geotagging pilots and APEDA’s Basmati.Net, traceability is becoming enforceable, not optional,” explained Shivani Singh, Program Coordinator for Law and Critical Emerging Technologies at the Advanced Study Institute of Asia. “With DNA testing, QR codes, and blockchain already setting importer expectations, a mandatory GI logo is the critical reform needed to protect basmati’s authenticity, curb counterfeiting, and secure who earns premiums—and who loses market access—in global trade.”

Treating Basmati as a premium brand would require a radical shift in perspective. Instead of short-term domestic controls, the focus would move to value creation by positioning Basmati as a luxury grain, akin to Champagne in wine or Arabica in coffee, with branding that emphasizes heritage, aroma, and exclusivity. It would also mean building resilience against rivals like Pakistan, which is aggressively marketing organic and SRP-certified Basmati, and Thailand, which has successfully branded Jasmine rice. Finally, policy stability is essential—creating predictable export regimes that reassure buyers and prevent sudden shocks to trade flows.

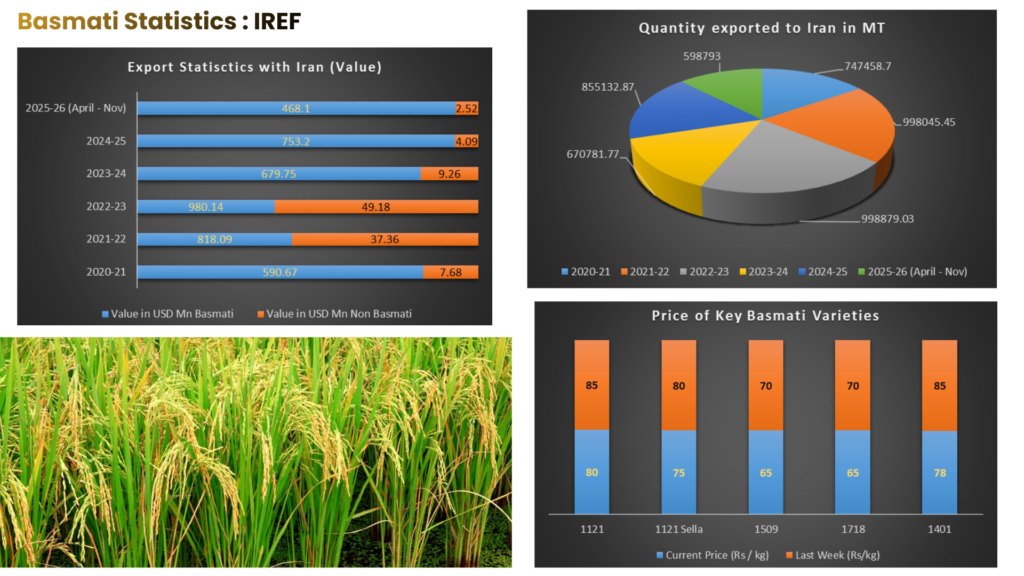

” Iran has been a key market for Indian basmati rice from an export perspective. Rice exporters have observed significant consumer demand in this region. When trade with Iran was fully open, KRBL was exporting around 250,000 tonnes of basmati rice to the market. However, over the years, sanctions and increased market restrictions have considerably impacted our business. Today, our current exposure to the Iran market is limited at around $8-10 million and is being managed prudently. Considering the limited trade to Iran, we have been doing majority of our trade through UAE, where Iranian importers operate local ”

—- Akshay Gupta, Head of Bulk Exports at KRBL Limited

Industry insiders warn that India’s current trajectory risks eroding Basmati’s global standing. “Over the past decade, Indian basmati exports have increasingly shifted toward lower-priced varieties, bulk shipments, and volume-led strategies. While export volumes have grown, average realisations have fallen sharply—from about $1,100–1,200 per metric tonne to $900–1,000. This value erosion risks positioning basmati alongside varieties like Thai Hom Mali or U.S. CalRose, despite its superior quality and cooking attributes. If left unchecked, the very characteristics that underpin basmati’s global demand could steadily weaken,” cautioned Akshay Gupta, Head of Bulk Exports at KRBL Limited.

The choice before India is stark. As a commodity, Basmati risks being dragged into price wars, its heritage diluted and its margins eroded. As a premium brand, it can transcend volatility, command loyalty in discerning markets, and stand as a symbol of India’s agricultural excellence. India must decide whether Basmati will remain a pawn of food inflation management or rise as the crown jewel of global agri-trade.

Policy Volatility and Export Stagnation

India’s basmati rice trade is entering a fragile phase, where policy uncertainty, geopolitics, and shifting buyer expectations are beginning to weigh on a segment long defined by premium positioning. “Every time India imposes sudden curbs on basmati exports, it signals unreliability to global buyers,” said Garg. “The 2023–24 ban handed Pakistan a ready opening, forcing Gulf states and Iran to shift suppliers and weakening India’s premium grain reputation.”

Export data reflects this strain. Between April and November FY26, rice exports were valued at $7.3 billion, only marginally higher than last year’s $7.29 billion. November saw a sharp contraction, with shipments falling to $0.79 billion from $1.12 billion a year earlier—despite FY25 being a record year with 19.86 million tonnes worth $12.47 billion.

Multiple headwinds are converging. The collapse of the Iranian rial, withdrawal of food import subsidies, and regional instability have softened demand. Adding to the uncertainty is US President Donald Trump’s proposal of a 25 per cent tariff on countries trading with Iran. While food is not directly targeted, exporters fear indirect fallout—payment delays, higher transaction risk, and weaker buyer confidence.

Iran remains a critical basmati market. The Indian Rice Exporters Federation warns that rising pressure could slow orders and delay shipments, hurting exporters and farmers alike. “Iran was once a cornerstone market for us, with KRBL exporting nearly 250,000 tonnes annually,” said Gupta. “Sanctions have reduced this to just $8–10 million, now largely routed through the UAE. The proposed US tariff adds yet another layer of risk for India’s basmati sector.”

Despite the slowdown, India retains scale. Volza data shows 66,801 basmati shipments between June 2024 and May 2025, up 10 per cent year on year. May 2025 was exceptional, with shipments rising 63 per cent. India remains globally dominant with 245,265 shipments, far ahead of Pakistan and China. But Pakistan’s aggressive pricing and sustainability branding are narrowing the gap.

“GI status gives basmati its identity, but without DNA testing, organic certification, and digital traceability, that identity is questioned,” Garg said. “Buyers now pay for trust as much as grain.”

Industry leaders argue that the solution lies in strategy, not scale. “The future lies in balancing basmati’s premium identity with sustainable growth—by prioritising consumer packs and quality-led differentiation over bulk exports,” Gupta said. “Traceability is no longer optional. At KRBL, we have implemented end-to-end traceability to the last mile because authenticity is non-negotiable.” With government rice stocks at a record 57.57 million tonnes, intensifying global competition, and rising geopolitical risk, India’s leadership in basmati will hinge on predictability, branding, and enforceable traceability—rather than volume alone.

India vs. Pakistan: Competitive Edge and Risks

India’s advantage in basmati remains scale and infrastructure. In 2023, it exported over 4 million tonnes, supported by advanced milling capacity and a mature export ecosystem. Pakistan, however, is closing in fast. In FY25, its basmati exports rose 30 per cent to 416,491 tonnes worth $434 million, driven less by volume and more by strategic portfolio positioning.

“India’s leadership in the basmati market rests on its heritage, scale, GI recognition, and its position as the world’s largest exporter, with over 5.2 million tonnes valued at nearly USD 5.8 billion exported in 2023–24. However, this dominance is increasingly contested. Higher tariffs in the United States, tighter regulatory scrutiny in the European Union, and ongoing geopolitical competition with Pakistan have turned basmati into both an agricultural and strategic issue. As other rice-producing nations strengthen traceability, quality controls, and branding to position their aromatic rice as premium alternatives, India’s ability to retain its leadership will depend on stronger enforcement and credible farm-to-export traceability systems.”

— Khushi Kesari, Program Officer at the History Lab, Advanced Study Institute of Asia

“The real advantage India holds is scale and diversity—149 million tonnes of paddy, unmatched varietal breadth, and an export ecosystem of 18,000 firms,” said Garg. “Indian exporters serve every major market, often with highly differentiated products.”

Pakistan’s edge lies in how it is pricing and branding its basmati portfolio. For the 2025–26 crop year (as on January 9), conventional Super Basmati is priced aggressively—around $885 per tonne for brown and $985 for milled—keeping it competitive whenever India raises its MEP. Parboiled variants range up to $1,085, while newer 1121 varieties command premiums of $1,125–1,175, signalling successful varietal upgradation.

” When it comes to the centuries-old heritage and economic significance of Basmati rice, a mandatory GI logo is, in fact, the critical reform needed to safeguard its authenticity, to put India’s global branding efforts, and to cut down on counterfeiting. For basmati, these tools will shape who earns premiums and who loses market access “

— Shivani Singh, Program Coordinator for Law and Critical Emerging Technologies at the Advanced Study Institute of Asia

At the premium end, Pakistan is monetising sustainability. Organic basmati is priced at $1,085–1,160, targeting EU demand, while SRP-certified basmati—marketed as climate-smart and traceable—is priced at $935–1,035, securing access to sustainability-sensitive markets. This dual strategy gives Pakistan flexibility: price leadership at the lower end and brand building at the higher end. India, by contrast, faces rising scrutiny over water use, methane emissions, and traceability gaps.

“India’s basmati strength lies in heritage, scale, and GI recognition, but tariffs and EU scrutiny make it a geopolitical issue as much as an agricultural one,” said Khushi. “Without credible farm-to-export traceability, that advantage weakens.”

The takeaway is clear. India’s premium position depends on policy stability, GI enforcement, and climate-smart traceability. Without these, Pakistan’s aggressive varietal innovation and sustainability-led pricing could steadily erode India’s dominance—not just in price-sensitive markets, but in the premium segments that define basmati’s global value.

Commodity or Crown

Basmati is more than a premium grain—it is a strategic national asset. “It provides fiscal relief, strengthens farmer incomes, and gives India leverage in global food diplomacy,” said Garg. Turning basmati’s heritage into national strategy is now critical.

At the farm level, the economics are clear. Priced around Rs 50 per kg, basmati delivers far stronger margins than non-basmati rice, reducing dependence on subsidies. Value then compounds beyond the farm gate, as millers grade output into Head Rice, Tibur, Dubar, and Mogra, each targeting distinct markets. This segmentation boosts margins but also raises exposure to branding and distribution risk.

“India’s edge lies in scale, seed R&D, and superior milling,” said Gupta, but that advantage is increasingly filtered through sustainability. “Protecting basmati’s premiumness is essential for long-term value and global brand equity.”

Sustainability is also the sector’s biggest vulnerability. “Water-intensive cultivation and chemical overuse in Punjab and Haryana have pushed ecosystems to the brink,” Garg warned. Without DSR, AWD, and integrated pest management, India risks regulatory backlash and reputational damage in key markets.

The value gap remains stark. “The premium is captured beyond the farm gate,” said Shivani. “Farmers face volatility, while exporters preserve value through ageing, branding, and access to EU and US markets. Weak GI enforcement and poor traceability mean the brand moves—but the returns don’t.”

Buyers are now demanding proof, not promises. “With groundwater overexploited and the EU tightening pesticide norms, water efficiency and low chemical use are non-negotiable,” said Khushi.

The path forward is narrow but clear: policy stability, farmer-centric incentives to shift from MSP-driven non-basmati to premium basmati, and enforceable GI, digital traceability, and climate-smart cultivation. Get it right, and basmati can anchor India’s premium agri-brand globally. Get it wrong, and it risks slipping into commodity parity with Pakistan and Vietnam.

—- Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)