Friday, 13 February 2026

Image Source: ImagineArt

In the lush, rain-soaked interiors of Kerala, the highlands of Davao, and the central provinces of Vietnam, a quiet agricultural revolution is taking root: Cocoa. Once relegated to the margins of local farming systems, cocoa cultivation in Asia is now at an inflection point. As the global chocolate industry confronts climate risk, ethical sourcing demands, and price volatility, the emergence of Asia’s cocoa belt has the potential to reshape global supply chains long dominated by West Africa. However can India, Vietnam, and the Philippines meaningfully challenge the African stronghold?

This article unpacks the comparative advantages and constraints of the Asian cocoa triangle, drawing on global benchmarks, climate suitability, yield gaps, processing capabilities, and export competitiveness to assess whether Asia is poised for a cocoa renaissance — or merely a supplementary footnote to Africa’s dominance.

Asia Munches, Africa Harvests: The Growing Divide in Cocoa Supply Chains

Cocoa’s global supply chain has never been more imbalanced. On one end sits West Africa—the unrivaled engine of global cocoa production. On the other, Asia—a region devouring chocolate faster than it can grow the beans. The result: a fractured value chain where the origin earns pennies and the processors, retailers, and brand owners capture billions.

In Ghana, cocoa isn’t just agriculture—it’s national identity. Roughly 800,000 farm families depend on it, generating nearly $2 billion in annual foreign exchange. Côte d’Ivoire, the world’s largest producer, relies even more heavily on cocoa: the crop made up 39 per cent of national exports in 2019, earned $5 billion, and supports six million people directly or indirectly.

Yet despite its dominance in raw output, West Africa remains trapped at the bottom of the value ladder. Côte d’Ivoire exports 72 per cent of its beans unprocessed; Ghana, 68 per cent. Most local processing is limited to cocoa liquor or butter, missing out on the high-margin chocolate products that drive the $45 billion global cocoa economy—expected to hit $61 billion by 2027.

Meanwhile, across the Indian Ocean, Asia’s appetite for chocolate is exploding. According to Euromonitor, the Asia Pacific region is now the world’s largest consumer of chocolate-infused goods—biscuits, cakes, pastries, ice creams. But while demand soars, supply is crumbling. Asia’s cocoa production has plunged from over 500,000 metric tonnes (MT) a decade ago to under 300,000 MT today, largely due to Indonesia’s decline—once the world’s third-largest producer—now hobbled by aging trees, pest outbreaks, and a wholesale pivot to palm oil.

Still, Asia’s grinding capacity is booming. Cocoa processing has surged past 1.1 million MT annually, led by Indonesia (465,000 MT, up 60 per cent in 10 years) and Malaysia (375,000 MT, up 28 per cent). To feed their grinders, Asian processors are importing nearly 600,000 MT from West Africa and over 150,000 MT from Ecuador—whose exports to Asia have risen at an eye-popping 23 per cent annual clip.

The paradox is glaring: Asia is the fastest-growing cocoa market, yet it’s hemorrhaging self-sufficiency. But that tide may be turning. Spearheaded by the Cocoa Association of Asia (CAA) and corporate partners like Mars and Mondelez, a quiet cocoa revival is brewing. In Indonesia, over 500 nurseries are now producing 30 million seedlings annually. More than 200,000 farmers are engaged in rejuvenation efforts, planting new high-yield clones like BB, RHS, and Monica 1 & 2—developed by national research bodies BRIN and ICCRI—to push productivity from 700 kg/ha toward 1,500 kg/ha and beyond.

Still, the road ahead is steep. Many plantations remain stuck with aging, disease-prone trees. Regulation around planting material distribution is patchy. And with younger generations disillusioned by the sector’s hard labor and thin margins, succession risks loom large.

If Asia doesn’t act fast, it will remain a chocolate superpower wholly dependent on foreign beans. The fix won’t come from technology alone. It requires integrated policy support, investment in farmer extension, harmonized quality control, and incentives to make cocoa farming attractive again.

In the current global split, West Africa grows the beans but sees little of the profit. Asia consumes the products but has neglected the crop. A new balance is overdue—one where producing nations capture more value and Asia becomes not just a chocolate market, but a cocoa powerhouse in its own right.

Cocoa 2.0: Asia’s Next Agri-Investment Goldmine

Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana supply nearly 60 per cent of the world’s cocoa—2.2 million and 750,000 metric tonnes (MT) respectively in 2023–24. Yet average yields remain stuck at 350–500 kg/ha due to aging trees, low adoption of improved inputs, weak extension systems, and intensifying climate risks. With small farm sizes of 2–3 hectares and limited replanting incentives, most farmers struggle to rise above subsistence-level returns, even as global cocoa prices surge.

In contrast, Vietnam has emerged as Asia’s cocoa yield trailblazer. Vietnam’s cocoa sector, though modest in scale, is emerging as a promising model for sustainable agriculture. Producing just under 4,000 metric tonnes in 2024, it contributes only 0.1 per cent to global supply, yet its beans enjoy “fine flavour” recognition by the International Cocoa Organization. As climate disruptions shrink African output and prices triple, Vietnam is leveraging global demand for high-quality, traceable cocoa.

Domestic players like Marou and Puratos are investing in farmer training, fermentation infrastructure, and traceability, helping expand cultivation across provinces such as Gia Lai and Binh Phuoc. Cocoa yields, now at around 1 tonne per hectare, could quadruple with improved agronomy and inputs. Pioneering circular practices, Helvetas Vietnam has introduced 14 regenerative models and trained over 1,100 farmers, while catalysing $115,000 in green investments. With EU deforestation rules approaching, Vietnam has a golden window to position itself as Asia’s zero-waste, premium cocoa hub—blending ecological integrity with commercial opportunity.

The Philippines, centered around Mindanao, is also showing promise. Average yields range from 600 to 900 kg/ha, with well-managed farms pushing 1,500 kg/ha. Cocoa production in the Philippines is currently cheaper than imports, making local beans competitive under an import substitution strategy. However, this edge is fragile—a mere 9 per cent drop in yield (currently 1.5 MT/ha) would erase the advantage. On the flip side, just a 2 per cent rise in yield or a 2 per cent cut in domestic costs could make the country export-competitive. The message is clear: with minor gains in productivity or efficiency, the Philippines could shift from import reliance to becoming a serious cacao exporter.

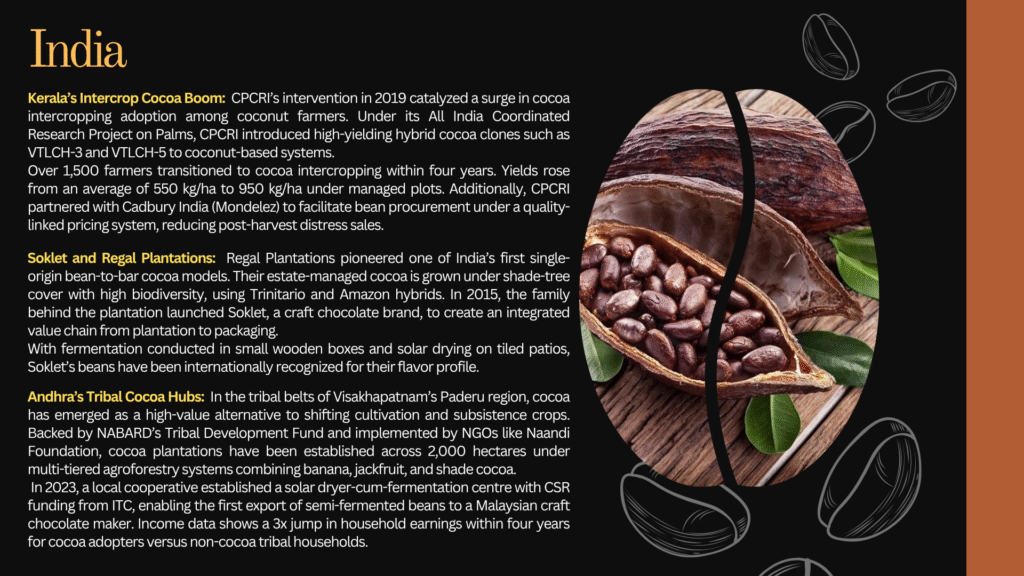

India, while a relatively small producer, demonstrates notable efficiency. Cocoa is cultivated as an intercrop under coconut and arecanut plantations in Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh, achieving yields of 750–1,000 kg/ha. India’s cocoa story is quietly transforming from a marginal agrarian subplot into a vibrant narrative of innovation and investment.

Between 2017 and 2024, production surged from 19,000 to 27,600 tonnes (CAGR: 4.8 per cent ), while cocoa acreage expanded from 83,000 to over 110,000 hectares—anchored by Andhra Pradesh (40.3 per cent) and Kerala (35.4 per cent). Intercropping within coconut and arecanut plantations has amplified its viability.

This momentum is matched by serious boardroom interest. Reliance acquired a 51 per cent stake in Lotus Chocolate for Rs 74 crore, Mondelez planning expansion by 5,000 hectares in partnership with CPCRI and Kerala Agricultural University, and Barry Callebaut looking forward its third-largest Asia-Pacific facility in Neemrana with a Rs 425 crore investment. ITC has also planned big, with Rs100 crore for its Haridwar factory and a luxury Fabelle unit in Bengaluru. Venture capital is swirling too—Rebel Foods acquired Smoor for Rs 426 crore, while LIL’ Goodness raised Rs 25.7 crore. Cocoa, clearly, is India’s next flavour frontier.

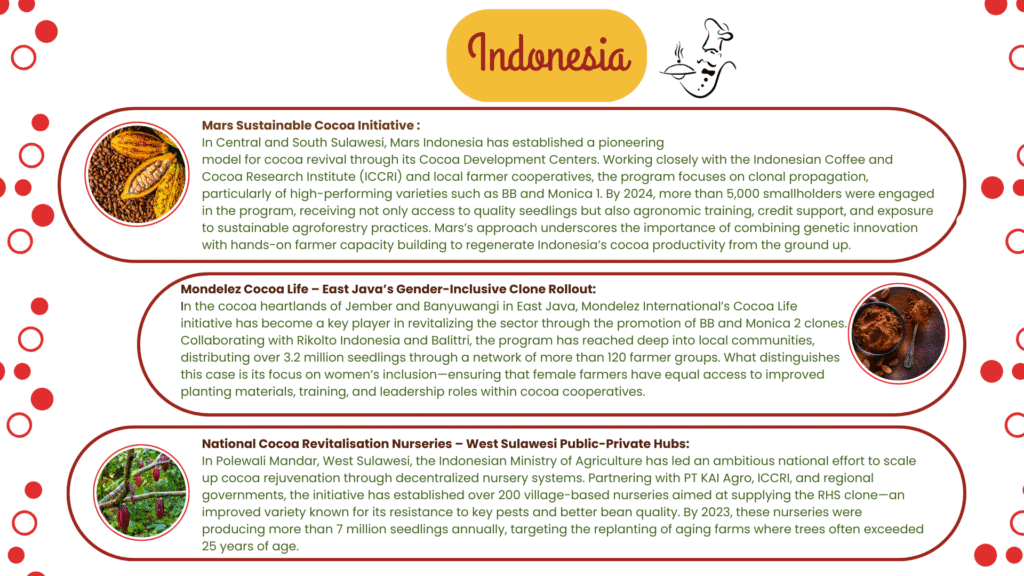

Indonesia, once the world’s third-largest cocoa producer, now lags behind due to declining yields of 550–800 kg/ha. Indonesia’s cocoa sector, once a global powerhouse, is navigating a slow but steady revival. Production is expected to reach 836,000 metric tonnes by 2026, growing at a modest 1 per cent annually—well below the historical average of 3.7 per cent since 1966. The decline in output allowed Ghana to surpass Indonesia in 2021, pushing it to the fourth spot globally.

Yet, even as local production inches upward, cocoa imports are accelerating. Indonesia is projected to import 354 million kilograms of cocoa by 2026, expanding at a 4 per cent compound annual growth rate. This growing import reliance reveals a deeper structural challenge: the country’s processing industry is outpacing its raw bean supply.

Indonesia, once a net exporter, is increasingly turning to West African and Latin American origins to meet the demands of its grinding sector. Unless farm-level productivity improves, the country risks becoming a cocoa processor dependent on foreign beans—rather than a self-sufficient cocoa economy. Industry-led partnerships are backing a major replanting push, with over 500 nurseries producing 30 million seedlings annually. New clones like BB, RHS, and Monica 1 & 2, backed by Mars, Mondelez, and public R&D institutions, aim to help Indonesia reclaim its place as Asia’s cocoa leader.

Export Competitiveness: Can Asia Capture Market Share?

While West Africa continues to dominate global cocoa production, the balance of export competitiveness is subtly shifting. As climate volatility, regulatory scrutiny, and aging plantations place increasing pressure on African suppliers, global buyers are actively scouting for reliable, traceable alternatives. This evolving market dynamic presents a pivotal opportunity for Asia—not through volume supremacy, but through value differentiation.

In 2024, Vietnam exported cocoa and derivative products worth approximately $180 million. Though its total production remains modest, Vietnam’s focus on fermented beans, semi-processed nibs, and traceability is helping it punch above its weight. The Philippines followed with $52 million in exports, driven largely by fine-flavor beans from Mindanao that cater to high-end chocolate makers in Japan, Europe, and the U.S. These two countries are laying the groundwork for a premium Asian cocoa identity—flavor-forward, origin-certified, and sustainability-aligned.

India’s cocoa sector, despite significant domestic investment, remains nascent in the export game. With exports under $5 million in 2024 and imports surpassing $150 million, India is still a demand-driven market. However, as fermentation and post-harvest infrastructure improve, Indian cocoa could emerge as a competitive origin for select specialty applications.

Indonesia, meanwhile, is diversifying its exports beyond raw beans into semi-finished products like cocoa butter, cake, and liquor. With grinding volumes outpacing production, the country is sourcing beans globally while maintaining a growing presence in downstream export markets.

What unites these Asian players is a strategic pivot toward capturing greater value per bean. Rather than chasing volume, they are targeting niche export segments—craft chocolate, couverture, and single-origin branded products—that command premium pricing. As the world’s chocolate palate matures and ethical sourcing becomes non-negotiable, Asia’s high-quality, climate-resilient cocoa could position the region as a future epicenter of sustainable, value-added cocoa trade.

Policy and Investment: What’s Missing in Asia’s Cocoa Strategy?

To genuinely challenge African dominance, Asian countries need a coordinated policy-industrial strategy. The first priority should be establishing fermentation infrastructure that meets international standards, which is essential for accessing premium export markets. Governments must also invest in farmer aggregation, organizing smallholders into cooperatives that enable traceability and scale. Financing instruments, especially for women and tribal cocoa farmers, are necessary to encourage investment at the farm level.

Further, public R&D should focus on developing pest- and drought-resistant cocoa clones tailored to local conditions. Logistics, including post-harvest drying and cold chain infrastructure, must be upgraded to reduce spoilage and enhance quality. Governments could incentivize export-oriented processing, including origin labeling and GI certification, to capture more value domestically. Certification schemes aligned with EU sustainability standards are also crucial as regulations tighten in global markets.

In India, the Cocoa Board must be reimagined to support both domestic industry and export readiness. The Philippines would benefit from a deeper blend of public and private investment, and Vietnam must guard against regional overconcentration that could create localized supply shocks.

Conclusion: The Asian Cocoa Century?

Asia will not overtake Africa in cocoa production volume any time soon—nor should that be its primary ambition. Competing on tonnage in a market long dominated by Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana is both unrealistic and economically shortsighted. Instead, the more strategic and high-return path lies in owning the premium end of the cocoa spectrum—traceable, fine-flavor, climate-smart, and ethically sourced. In this niche, countries like Vietnam, India, and the Philippines already display a confluence of competitive advantages: Quality-focused agronomy, expanding processing capacity, and increasing investor confidence.

What Asia lacks in legacy scale, it can compensate for with agility, innovation, and alignment with evolving global norms. The international cocoa trade is being reshaped by powerful forces—deforestation-free mandates from the European Union, rising demand for craft and bean-to-bar chocolate, and an urgent pivot toward climate resilience. These pressures are beginning to unravel the traditional model of high-volume, low-value cocoa farming. This is where the Asian cocoa triangle has a historic window: To build a new blueprint from the ground up.

Vietnam is already positioning itself as the poster child for fine-flavor, traceable cocoa—with regenerative practices, GI potential, and fermentation infrastructure tied to premium buyers. The Philippines has the opportunity to scale sustainably and cost-effectively in Mindanao, while also pushing into export markets with artisanal beans. India, with its strong FMCG sector, intercropping models, and R&D ecosystem, is uniquely placed to marry domestic consumption with selective export capability.

However, unlocking this potential won’t be automatic. It will require smart policy coordination, deep investment in farm-to-factory infrastructure, and a rethinking of how value is captured and shared across the supply chain. Governments must work with industry leaders to upgrade fermentation systems, aggregate smallholders, and standardize post-harvest protocols. Traceability should not be seen as a burden but as a competitive edge. Financing must be made accessible not just to large processors but to women, youth, and tribal cocoa farmers at the grassroots.

If this transformation takes hold, Asia’s cocoa story will not be one of catching up—but of leapfrogging. Rather than remaining a passive consumer market or an isolated origin, the region could emerge as a hub of sustainable, value-added cocoa production, dictating new standards for quality, ethics, and resilience.

The global cocoa belt is shifting—and this time, Asia is no longer on the sidelines. It’s preparing to lead.

——————————- Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)