Insurance and forecasts could be used as climate adaptation strategies for farmers: Study

A new study by Burlig and her University of Chicago coauthors—Amir Jina, Erin Kelley, Gregory Lane and Harshil Sahai finds that providing farmers with an accurate weather forecast of the monsoon onset can help farmers decide how much to plant, what to plant, or whether to plant at all.

Climate change is making weather more variable, jeopardizing the livelihoods of the majority of the world’s poor who depend on agriculture for survival. Highly variable weather makes it challenging for farmers to prepare for the coming season because they don’t know if this year will be like the last. But a new study from India finds that providing them with an accurate weather forecast—in this case, of the monsoon onset—can help farmers decide how much to plant, what to plant, or whether to plant at all. Nearly two-thirds of the global population live in monsoon-affected regions.

“Farmers tailor their planting decisions based on what they think the weather—and in many parts of the world, the monsoon—will be like, but climate change is making the monsoon and other weather patterns increasingly difficult to predict,” says study co-author Fiona Burlig, an assistant professor at the Harris School of Public Policy and deputy faculty director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago’s India office. “Our study, from an Indian state where agricultural productivity per worker is generally low, found that new forecasts are able to deliver accurate monsoon predictions even in a changing climate. Farmers listen to these forecasts and are able to change their planting decisions, accordingly, making them an important climate adaptation tool for the agricultural sector.”

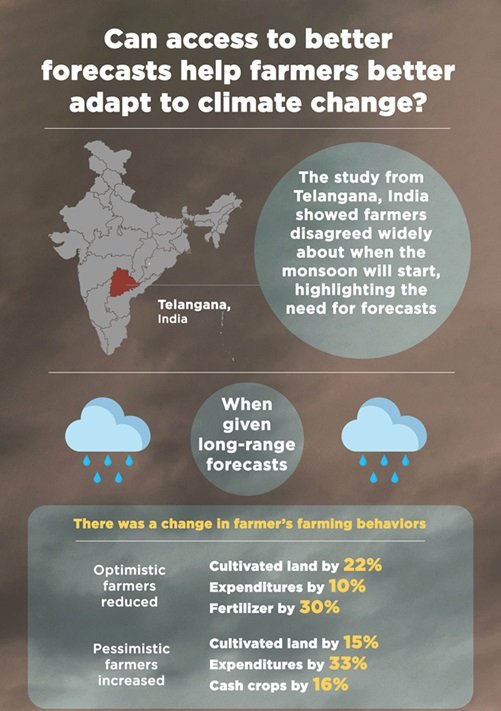

Burlig and her University of Chicago coauthors—Amir Jina, Erin Kelley, Gregory Lane and Harshil Sahai—studied how farmers across 250 villages in India’s Telangana state changed their behaviors when given highly-accurate forecasts (at least 4-6 weeks ahead) on when the annual monsoon would begin. An earlier monsoon typically means a longer growing season, suited to cash crops like cotton. Later monsoons are generally worse, forcing farmers to grow lower-value subsistence crops like paddy. To boost the credibility of the forecasts in the eyes of the farmers, the researchers partnered with the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics in Hyderabad.

On a pre-season visit to the Medak and Mahabubnagar districts of Telangana where the study was conducted, the researchers found that farmers’ predictions about when the monsoon would arrive varied widely. The more optimistic farmers believed the monsoon would come about 2.5 weeks earlier than the more pessimistic farmers. Then, they were given the more accurate forecasts. The new information changed their minds and their farming behaviors.

Overly optimistic farmers, for whom the forecast brought “bad news” of a shorter-than-expected growing season, took steps to cut down on their investments and expenditures. For example, they reduced the amount of land they cultivated by nearly a quarter and bought about a third less fertilizer than farmers with similar beliefs who received no information. While their agricultural output, crop sales and farming profits took a hit because they engaged in less farming overall, these farmers also tended to find other ways to make money. As a result of receiving the forecast, four out of seven of them newly owned a non-agricultural business, and as a group they cut their debt in half, leading to net savings of more than $560 per farmer and an almost doubling of their business profits. In other words, instead of doing unprofitable farming, they were able to diversify their activities—the forecast made these farmers better off.

Overly pessimistic farmers, for whom the forecast brought “good news” that the growing season would be longer than expected, increased investments and expenditures. For example, they increased the land they cultivated by 15 percent and were more likely to add new crops and cash crops. This led to 22 percent increases in agricultural production.

The researchers also tested how giving farmers insurance—which is highly promoted by the Indian government—instead of forecast information would change their behaviors. Overall, farmers who received insurance increased the land they cultivated and the amount they spent on up-front investments like seeds and fertilizer. These effects were driven by overly optimistic farmers, who incorrectly believed it would be a good year. Given the safety net the insurance provided, they responded with a large increase in investments—even though the forecast would have caused them to instead reduce investments. In this way, insurance and forecasts could be used as complimentary climate adaptation strategies: Forecasts let farmers make the right investments for the coming year, while insurance protects them against risk.

“We saw a direct line from more accurate forecast information to improved investments for farmers—and, more prosperous farmers mean a healthier economy,” says study co-author Gregory Lane, an assistant professor at the Harris School of Public Policy. “Countries have a huge opportunity to help protect their farmers and their economy from the unpredictability of climate change by improving their long-range forecasts.”

A new study by Burlig and her