Monday, 2 February 2026

For decades, millets have existed on the periphery of the Americas’ grain economy — overshadowed by corn, wheat, and soy. Yet as climate volatility reshapes agriculture, these resilient cereals are emerging as a strategic hedge for food security, farm profitability, and market diversification. With rising drought frequencies, declining soil fertility, and shifting consumer preferences toward gluten-free and low-GI foods, millets now sit at the crossroads of agricultural adaptation and food innovation. While their presence in North America is modest — planted largely for forage, birdseed, and niche ethnic markets — and in South America is still embryonic, the fundamentals point to untapped potential. The next decade could see millets move from a marginal crop to a mainstream pillar in the Americas’ agri-food system, if market signals and policy incentives align.

Proso Millet: The Climate-Smart Workhorse

Among the various millet species, proso millet (Panicum miliaceum) has perhaps the strongest case for rapid scale-up in the Americas. With a short maturity cycle of just 60–70 days, proso millet thrives where corn and wheat often fail — particularly in drought-prone, low-fertility regions. In the U.S., production is concentrated in the western Great Plains, with Colorado, Nebraska, and South Dakota leading.

According to USDA data, U.S. farmers plant between 200,000 and 300,000 acres annually, yielding an average of 1,000–1,200 pounds per acre. The crop’s low water requirement — approximately 30–35 per cent less than sorghum and 50 per cent less than corn — makes it an insurance policy against erratic rainfall. In Brazil’s semi-arid Cerrado and Argentina’s Chaco, proso millet trials have shown comparable drought resilience, with yields holding steady where maize lost 30–40 per cent due to heat stress. This positions proso millet not only as a stopgap in bad years but as a strategic rotation crop to stabilize farm incomes.

Pearl Millet: Versatility Beyond Forage

Pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum), traditionally associated with livestock feed in the U.S., is steadily breaking geographic and market boundaries. Known for its ability to withstand both high heat and sandy soils, pearl millet is now grown as far north as southern Canada. In the southeastern U.S., it is valued for its role as a summer forage crop, reducing pest pressures and improving soil health when rotated with cotton, peanuts, or soybeans. Recent trials in Kansas and Ontario show promise for grain use — with protein content of 12–14 per cent and iron levels surpassing wheat — making it a candidate for gluten-free food processing.

In Brazil’s Minas Gerais and Goiás states, pearl millet is gaining traction as a dry-season forage, often double-cropped after soy, but there is early-stage interest in processing it for human consumption, especially for health-conscious urban markets. The pivot from forage to food hinges on milling infrastructure, breeding programs for culinary traits, and sustained market demand.

The Untapped Potential of Other Millets

Beyond proso and pearl, a range of other millets — including foxtail (Setaria italica), barnyard (Echinochloa spp.), and finger millet (Eleusine coracana) — remain underexploited in the Americas. In the U.S., these crops are largely relegated to cover crop mixes or niche birdseed blends. Yet their agronomic benefits are significant: foxtail millet’s rapid canopy cover suppresses weeds; finger millet’s exceptional calcium content (10x that of rice) offers a nutritional marketing edge; and barnyard millet’s tolerance to waterlogging makes it unique among dryland cereals.

In Paraguay and northern Argentina, smallholder farmers are experimenting with millet as a multi-purpose crop — part forage, part grain — to spread climate risk. The gap lies in varietal development and commercialization pathways. If breeding programs focus on yield stability, grain size, and milling efficiency, these secondary millets could graduate into higher-value markets such as bakery blends, breakfast cereals, and functional snacks.

Millets Mean Markets: The Commercial Bottleneck

Across the hemisphere, farmer interest in millets is higher than planting statistics suggest. Surveys conducted by Colorado State University in the U.S. and Embrapa in Brazil reveal that over 40 per cent of interviewed farmers would consider growing grain millets if reliable market channels existed. The main constraint is not agronomy but economics: without established procurement networks, farmers face the risk of unsold harvests or having to accept low feed-grade prices.

In the U.S., most proso millet for human consumption is exported — primarily to birdseed markets in Europe and Japan — rather than processed domestically. In South America, the market is even less developed, with millet grain sales occurring mainly in informal or local barter economies. Building processing chains in tandem with market development is critical. That means investment in cleaning, dehulling, milling, and packaging infrastructure, alongside buyer commitments from food processors, brewers, and health food brands.

Innovation is Sprouting

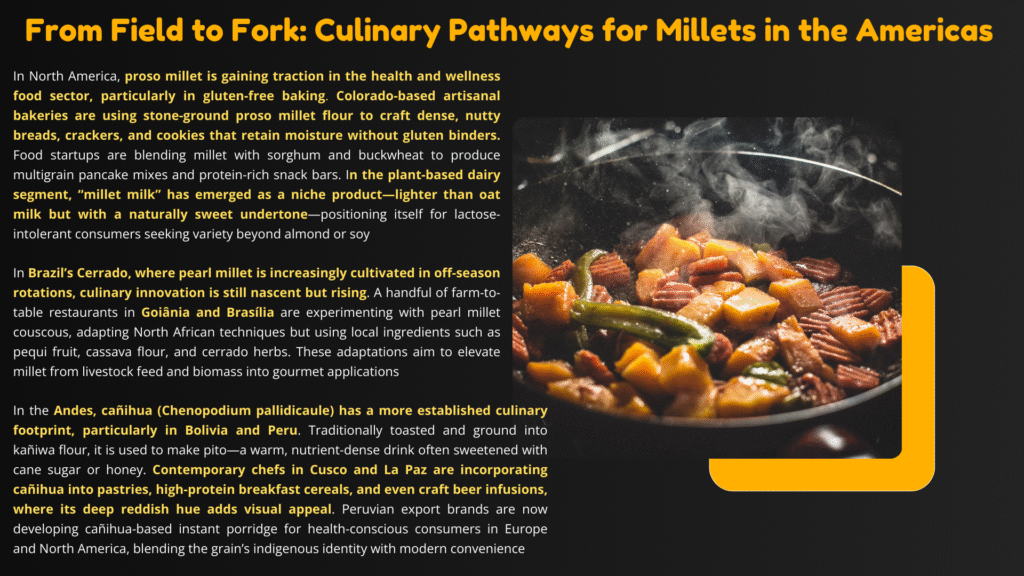

The consumer-facing side of the millet story is where the greatest growth potential lies. Millets’ gluten-free profile, low glycemic index, and high micronutrient content align perfectly with health and wellness trends. Yet in both North and South America, millets are still perceived by many as a specialty or ethnic food rather than an everyday staple. Innovation is starting to chip away at this image.

From an economic perspective, millet recipe innovation has a multiplier effect. It not only boosts direct grain demand but also creates opportunities for processing SMEs, gastronomy tourism, and export-oriented food brands. The U.S. gluten-free market alone is projected to exceed $7.5 billion by 2030, while South America’s functional foods segment is growing at over 6 per cent CAGR, offering fertile ground for millet-based product launches. However, scaling these culinary applications will require targeted investments in dehulling, milling, and packaging infrastructure—steps that remain bottlenecks in many millet-growing regions.

In the U.S., craft breweries in Colorado and Minnesota are experimenting with millet-based beers, targeting both celiac consumers and the “better-for-you” alcohol segment. In Canada, start-ups are developing millet flours for gluten-free baking mixes. In Brazil, millet is being trialed as a base for plant-based beverages, blending with fruits to create high-protein smoothies. The challenge — and opportunity — is to develop a product portfolio that serves multiple consumer segments: functional foods for the health-conscious, affordable staples for price-sensitive buyers, and indulgent products that make millets aspirational.

Next Steps for the Americas

If millets are to move from marginal to mainstream, the Americas will need a coordinated push across four fronts: research, crop improvement, product innovation, and market development. On the research side, North America can leverage universities like Kansas State and South Dakota State, while South America can build on Embrapa’s dryland cereal programs. Crop improvement priorities include breeding for yield stability under stress, improving grain uniformity for milling, and enhancing nutritional profiles. Product innovation requires collaboration between food scientists, chefs, and marketers to broaden millets’ appeal beyond the gluten-free niche. And market development will demand public-private partnerships to de-risk investments in processing and supply chains.

Globally, millets account for around 30 million tonnes in annual production, with Africa and Asia dominating output. For the Americas, even capturing 5–10 per cent of that market — whether through domestic consumption or exports — could represent a multi-billion-dollar opportunity. In an era of climate uncertainty, where resilience is as valuable as yield, millets offer the hemisphere a strategic grain for the next agricultural chapter.

— Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)