Monday, 23 February 2026

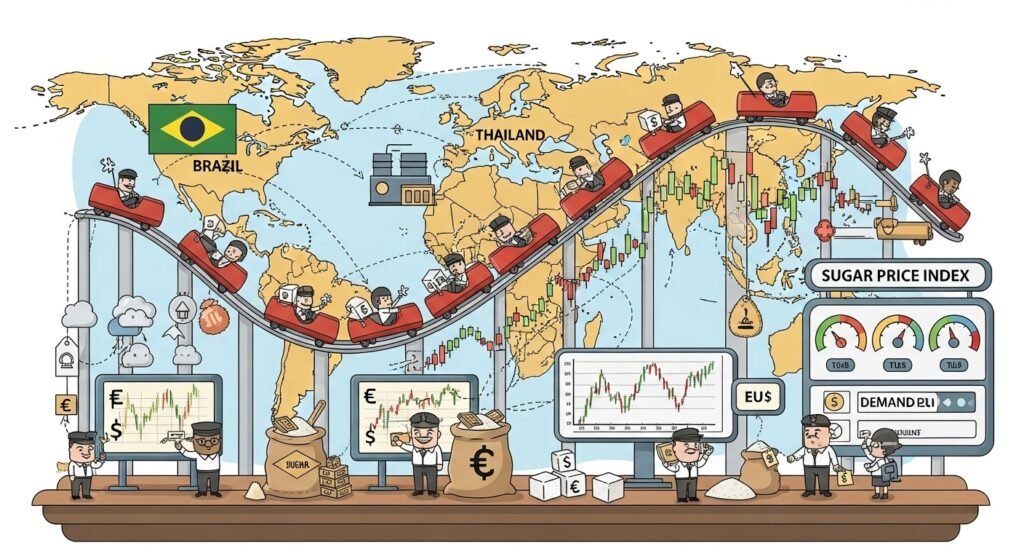

India’s sugar story in 2025 is a study in contrasts: After seasons of tight supplies and anxious policy bandwidth, the country is now staring at a meaningful surplus just as global markets — conditioned by a strong Brazilian crop and recovering Thai shipments — are already soft.

That surplus gives New Delhi leverage: A chance to stabilise domestic farmer incomes, to lock in foreign exchange from exports and to deepen a nascent energy strategy through ethanol. It also creates a policy dilemma. Over-export and India risks domestic price spikes; under-export and it leaves money on the table and misses an opportunity to shape global prices. Managing the 2025–26 sugar season will test the coherence of India’s sugar–ethanol strategy and the government’s ability to thread competing objectives — farmer welfare, mill viability, energy targets and trade commitments — into a single playbook.

The Arithmetic of Abundance

The numbers for India’s 2025–26 sugar season tell a story of opportunity, but also of delicate balancing. Production is projected to reach approximately 34.9 million metric tonnes (MMT), an 18 per cent increase over the previous year. This rebound reflects several favorable factors: A more evenly distributed monsoon across key cane-growing regions, higher sucrose recovery rates at mills, and incremental improvements in agronomic practices such as better irrigation, mechanised harvesting, and pest management.

Domestic sugar consumption remains relatively stable, estimated at 28.5–29 MMT. This steady demand ensures that the bulk of the increased output can be considered surplus — but the scale of the surplus is modest enough that it cannot be ignored. Between 4–6 MMT could be available for either export or diversion to ethanol production, depending on government policy and market conditions. This “free” volume represents both an economic opportunity and a policy responsibility: too aggressive an export push risks driving domestic prices higher, affecting millions of consumers; too conservative a strategy leaves foreign exchange and global market influence on the table.

” India’s projected sugar surplus for the 2025–26 season presents a strategic opportunity to harmonize domestic priorities with global market dynamics. The anticipated volume is expected to ease supply constraints and stabilize sugar prices both locally and globally. With the government’s continued push for crop productivity and favourable monsoon conditions, robust arrivals of paddy and maize are anticipated—enhancing feedstock availability for ethanol production.

The upcoming ethanol year will spotlight how feedstocks are allocated, with expectations of a well-rounded approach that supports a long-term pivot to strategic, climate-resilient feedstocks, ensure consistent demand for farmers, and enables financial sustainability for ethanol producers. Overall, the outlook suggests a seamless supply scenario across applications – including exports, benefiting farmers, mills, and consumers alike.”

— Puneeth Kumar K T, Business Director, Planetary Health Biosolutions, South Asia, Novonesis

Closing carry-over stocks are projected at around 5 MMT, sufficient to provide a buffer against sudden shocks such as weather disruptions or a spike in domestic demand during festivals. Yet the buffer is not so large as to remove the need for active management. The combination of high production, steady domestic demand, and moderate carry-over positions India at a strategic inflection point. It can comfortably meet domestic needs while freeing up several million tonnes for other productive uses, including export markets and ethanol blending.

In short, India’s sugar sector in 2025–26 finds itself in a sweet spot: Enough surplus to influence global markets and provide a stable revenue stream for farmers and mills, but not so much that policy choices can be deferred. Navigating this arithmetic carefully will determine whether the season’s abundance translates into economic gains, energy security, and market credibility, or whether it becomes another cycle of policy stress and reactive interventions.

Who Wins and Who Loses at Home

The domestic dynamics of India’s sugar sector in 2025–26 are defined by a clear divide between farmers and mills, each facing distinct opportunities and risks. For farmers, the larger cane crop this season, coupled with continued government procurement support, should improve liquidity across cane belts and reduce the immediate risk of distress that has historically followed supply shocks. Timely payment of cane arrears — long considered the cornerstone of farmer welfare — remains critical.

However, the ability of mills to meet these obligations hinges on their cash flows. If global sugar prices soften sharply, mill revenues may be squeezed, creating a scenario where arrears re-emerge as both a political and humanitarian challenge. Here, ethanol diversion plays a stabilising role. Ethanol offtake is generally more predictable than raw sugar exports, backed by government procurement and less subject to price swings, allowing mills that expand ethanol capacity to mitigate some of the market risk associated with farmer payments.

Mills themselves face a structural divergence. Those equipped with ethanol production and co-generation facilities are positioned as clear winners this season. Ethanol provides a defined, policy-driven demand stream and often yields higher and more stable margins than selling sugar into an already soft global market. By contrast, mills without distillation or co-generation capabilities are exposed to global price volatility and may struggle to maintain cash flow stability.

Smaller sugar-only mills, in particular, are likely to lobby for export windows that allow them to monetise inventories before ethanol economics become dominated by larger, integrated players. This creates a tension between large ethanol investors, who benefit from long-term policy-driven demand, and smaller mills seeking short-term market relief — a key axis of lobbying and policy debate in the coming season.

In essence, the winners are those who can integrate sugar and ethanol production, leveraging government-backed demand to stabilise revenues, while the less-equipped players risk marginalisation unless policy interventions, such as targeted export quotas or credit support, are provided. Balancing these interests will be crucial to maintaining both industry viability and farmer welfare in a season of surplus.

Global Ripples — Supply, Demand and Prices

India’s sugar export capacity has grown to a scale that gives the country genuine influence over global markets. If policymakers allow 4–5 MMT of sugar to be exported this season, it would add significant tonnage to an already well-supplied global market, exerting downward pressure on international raw sugar futures in the near term. Traders have already been reactive: Recent price trends show that the prospect of stronger shipments from India, coupled with recovering exports from Thailand and a robust Brazilian crop, has softened both ICE raw sugar and London white sugar futures. This suggests that markets are highly sensitive to shifts in supply from major players, and India’s policy choices could therefore directly shape price trajectories.

Lower global sugar prices bring immediate benefits for import-dependent countries and multinational food and beverage companies, who gain access to cheaper raw material. However, smaller exporters — particularly those without integrated logistics or scale advantages — may find themselves squeezed, unable to compete on cost and efficiency. This asymmetry could reshape competitive dynamics in the global sugar trade, reinforcing the advantages of large-scale, policy-aligned exporters like India.

Beyond economics, Indian sugar exports carry geopolitical weight. Steady shipments can act as a stabilising tool for the region, helping neighbours such as Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and select Middle Eastern countries manage food inflation and avoid domestic shortages. Yet this influence comes with caveats: Aggressive price support or export subsidies could trigger scrutiny from trade regulators and raise questions under international trade frameworks. Balancing the dual objectives of global market influence and compliance with trade rules will be a central challenge for policymakers, who must weigh the economic benefits of exports against potential regulatory and reputational risks.

In short, India’s sugar policy choices this season will reverberate far beyond its borders. The country has the capacity to act not merely as a participant in the global sugar market but as a price shaper — a role that carries both opportunity and responsibility.

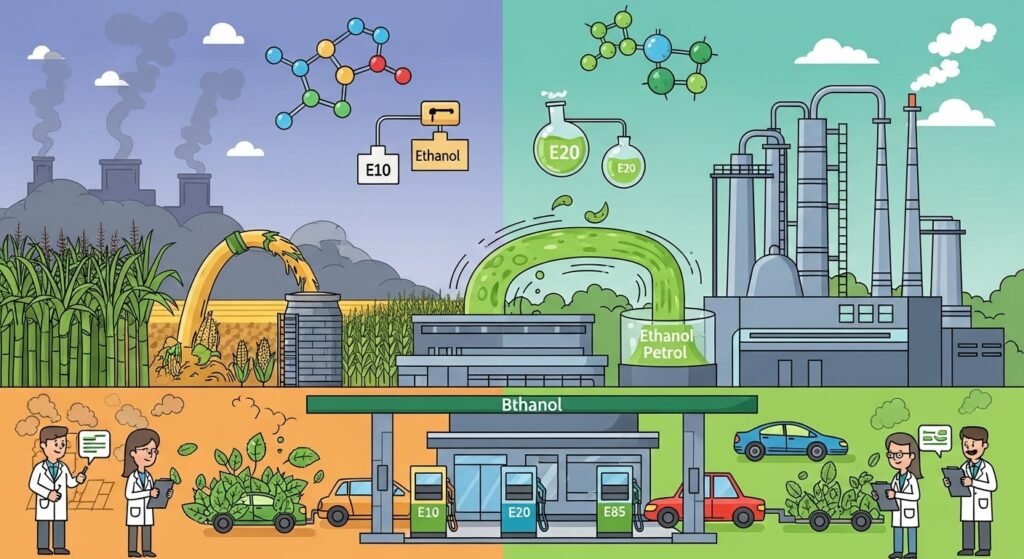

Ethanol: The Long Game that Rewrites Demand

Since the early 2020s, India has strategically deepened the link between sugarcane production and fuel policy, transforming ethanol from a niche byproduct into a structural component of both energy and agricultural strategy. The Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) programme has advanced rapidly, with blending rates reaching approximately 19 per cent by mid-2025 and policy targets set to achieve 20 per cent blending for the 2025–26 supply year. Meeting this target requires diverting a substantial portion of sugarcane sucrose — amounting to several million tonnes in sugar-equivalent terms — away from conventional sugar production toward ethanol.

This shift introduces a clear and high-stakes trade-off. Ethanol offers mills predictable, government-backed offtake and revenue, insulating them from the volatility of global sugar markets. It also supports India’s broader energy security goals, reducing reliance on imported fossil fuels, and contributes to national emission-reduction targets, aligning agricultural output with climate policy. However, the diversion of sucrose into ethanol inevitably reduces the volume of raw sugar available for both domestic consumption and exports. The scale of this diversion will influence domestic price stability, international competitiveness, and the ability of smaller, sugar-only mills to remain financially viable.

How India navigates this balance will shape its long-term role in global sugar markets. A carefully managed ethanol strategy could position India as a consistent absorber of sugar overproduction, stabilising domestic markets and generating predictable revenue streams for mills and farmers. Conversely, if ethanol diversion is underutilized or misaligned with market conditions, India risks remaining a cyclical exporter, reacting to price swings rather than shaping them, and leaving both domestic stakeholders and global markets exposed to volatility.

In essence, ethanol has emerged as a strategic lever, capable of redefining demand patterns, mitigating market risks, and aligning agricultural production with energy and environmental objectives — but only if policy and industry execution are calibrated with precision.

Policy Levers and Pragmatic Blends

Policymakers have multiple instruments at their disposal to balance competing objectives. Phased export tranches, for instance, could allow 2–3 MMT to be offered early in the season, with a mid-season reassessment providing both market visibility and flexibility to respond to weather or demand shocks. Maintaining a minimum closing buffer of 6–7 MMT would protect domestic prices during festival seasons and winter demand peaks.

Ethanol incentives can be designed to float with global sugar prices, making diversion more attractive when sugar prices fall and less so when export realisations are strong. Mills could be encouraged to hedge part of their sugar output via commodity exchanges, coupled with government-facilitated working capital support, to stabilise cash flows and ensure timely farmer payments.

Additionally, small sugar plants without ethanol capacity may require targeted credit lines or temporary export quotas to prevent arrears and closures. These measures collectively align economic logic with political realities: Predictable payments for farmers, steady revenues for mills, protection against food inflation, and credibility as a reliable exporter.

The Strategic Question

India has moved from being primarily a price taker to occasionally a price shaper in global sugar markets. The challenge is not just to clear surplus stocks but to convert cyclical abundance into structural resilience: Deeper ethanol markets, stronger mill balance sheets, and an export strategy that commands respect without destabilizing domestic markets. Success would translate this season’s abundance into durable benefits for farmers and the industry, while failure could trigger a repeat cycle of arrears, emergency policy interventions, and political fallout.

—- Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)