Friday, 20 February 2026

In an exclusive interview with Agrospectrum, Willy Gabriel Mboukem, President of La Green Factory, outlined how Africa can finally rewrite its role in the $130-billion cocoa economy. Speaking through the lens of Autour du Cacao, his flagship project, Mboukem stressed that the real breakthrough lies not only in local processing but in valorizing by-products—transforming husks, mucilage, and pulp into new industries from cosmetics to bioplastics. He argued that Europe’s new deforestation rules, while challenging, could be a springboard for African producers to lead on traceability and sustainability if backed with the right support. Looking ahead to 2035, he envisions a cocoa sector driven by prosperous farmers, strong cooperatives, and globally recognized African brands. But he warned that without investment, governance reform, and youth engagement, Africa risks remaining a raw bean supplier in a market it should be shaping.

The Value Paradox

Africa produces most of the world’s cocoa but captures little of the value. Why has this paradox endured, and what levers could finally shift value addition closer to origin?

The fact that Africa produces the vast majority of the world’s cocoa while capturing only a tiny fraction of its value is a persistent paradox, deeply rooted in colonial history and global economic structures. Several factors contribute to this.

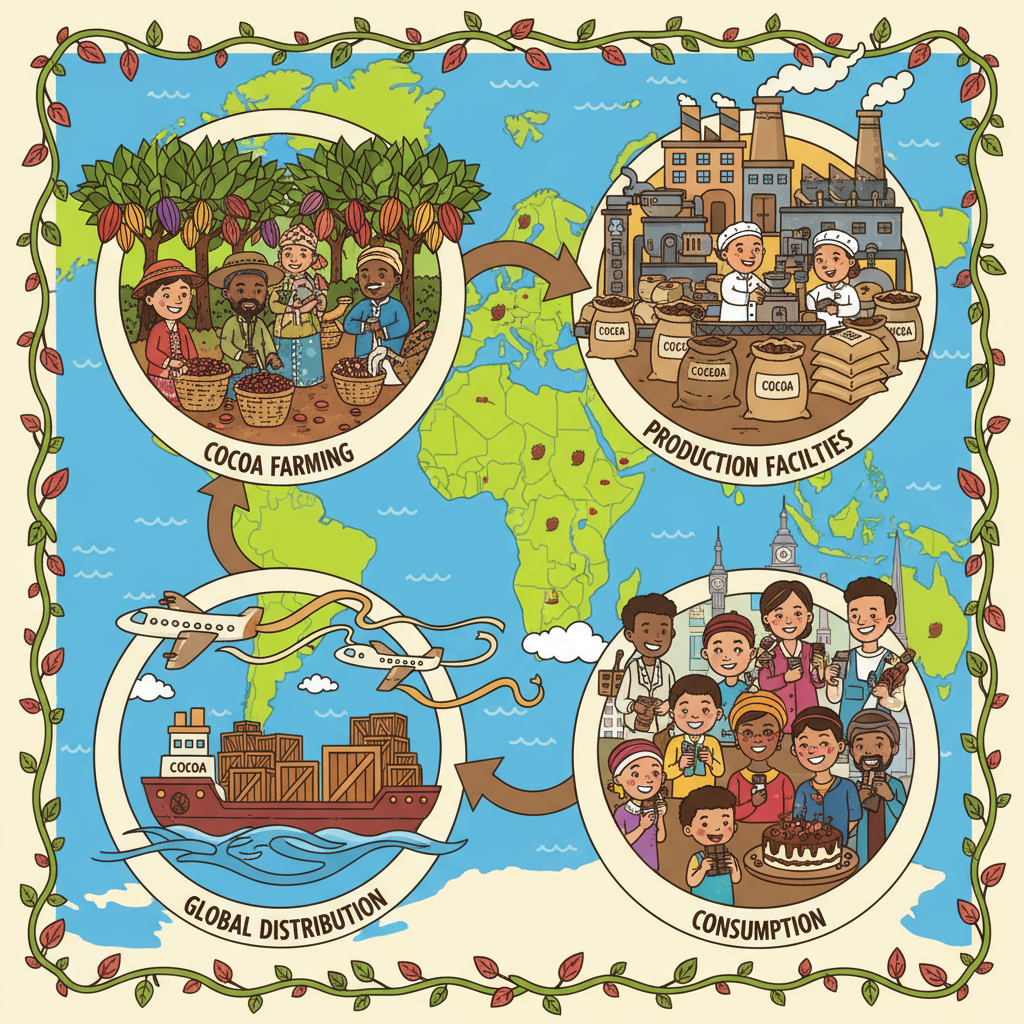

Historically, producing countries have been confined to the role of suppliers of raw beans, with little or no local processing. The value-added stages—roasting, grinding, chocolate manufacturing, and marketing—are predominantly captured by companies in consuming countries.

Insufficient investment in infrastructure (roads, energy, logistics) and limited industrial capacity further hinder the development of a competitive local processing industry. The cost of local processing can sometimes exceed that of exporting raw beans and importing finished products. However, Côte d’Ivoire is making tremendous progress on this front by canceling exportation of raw beans from April to October. This effort is designed to allocate beans to processors, with the goal of transforming 50 per cent of production by 2050.

African producers also often face difficult access to international markets for processed goods and lack information on consumption trends, quality requirements and export prices, making them dependent on intermediary buyers.

In addition, sanitary, phytosanitary, and quality standards imposed by importing markets can be difficult for small producers and emerging processors to meet, requiring costly investments and training.

A crucial but often overlooked factor is the low valuation of by-products. The industry focuses almost exclusively on the cocoa bean for chocolate production. However, the cocoa pod, mucilage, husk, and other parts of the fruit hold immense economic and nutritional potential, which often remains untapped. The failure to valorize these by-products represents a significant economic loss and waste of resources.

How to Change the Game?

The most powerful lever to shift value addition to the origin lies in diversification and valorization of cocoa by-products. It is imperative to move beyond the binary thinking of “cocoa = chocolate and beans.” The true wealth of cocoa does not lie solely in the bean. Mucilage can be transformed into juice, vinegar, or alcohol; the husk into biochar, fertilizer, bioplastics, or animal feed ingredients. The pulp can be used for refreshing beverages or jams. These transformations, often less capital-intensive than large-scale chocolate production, can be carried out locally, creating jobs, generating additional income for farmers, and reducing waste.

Our initiatives are dedicated precisely to highlighting these innovations and the actors who are exploring new valorization pathways. We interview entrepreneurs, researchers, and farmers who are transforming cocoa beyond the bean, demonstrating the economic and environmental potential of these by-products. It is by investing in research and development of these alternative value chains, training local populations in transformation techniques, and facilitating market access for these new products that Africa can finally capture a fairer share of its cocoa’s value.

Europe’s New Rules

The EU Deforestation Regulation is poised to redefine cocoa trade. Do you see it primarily as a compliance burden for African farmers or as a chance to accelerate traceability and sustainability?

The EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR) marks a turning point for the cocoa trade. I view it not as a compliance burden but as a rare opportunity to accelerate traceability and sustainability in the cocoa supply chain—so long as it comes with adequate support for producers.

A burden or an opportunity?

For African farmers, especially smallholders, the regulation will not be easy. Parcel geolocation, proof of non-deforestation, and due diligence bring new layers of complexity and cost. Without technical and financial backing, many could be shut out of the European market, with serious socio-economic consequences.

Yet the very stringency of the EUDR forces a transformation the industry has long postponed. Traceability, for decades little more than an aspiration, is now non-negotiable. By requiring precise data on origin, the regulation enables the identification of deforestation-risk areas, ensures cocoa comes from legal and sustainable sources, and strengthens the fight against child labor and other abuses.

Compliance will also accelerate the adoption of sustainable practices. Farmers will need to move toward methods that do not drive deforestation, pushing agroforestry, forest restoration, and more responsible land management from theory to practice.

The benefits extend beyond the farm. Demonstrating compliance with European standards could help African cocoa shed its reputation as a commodity plagued by sustainability concerns. Producers who meet the bar stand to gain buyer confidence and access to premium markets. And with regulatory clarity, investment in sustainable and traceable supply chains becomes more attractive, offering committed farmers a clearer pathway to long-term resilience.

The role of support

For this opportunity to outweigh the risks, substantial support is essential. Farmers will need technical assistance in GPS mapping, data management, and sustainable agronomic practices. They will require financial support—credit for equipment, certification, and transition costs. Local institutions must be strengthened so they can guide producers through compliance. And above all, there must be open dialogue between the EU, producing countries, and supply chain actors to ensure the regulation is implemented fairly and effectively.

If these conditions are met, the EUDR could do more than reshape trade. It could set the stage for a cocoa industry that is transparent, sustainable, and more equitable—one in which Africa positions itself not at the margins but at the forefront of responsible production.

Processing Ambitions

Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana have set targets to process more of their cocoa locally. In practical terms, what stands in the way of Africa scaling beyond semi-processing into globally competitive chocolate?

The ambitions of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana to process more of their cocoa locally are both commendable and necessary if Africa is to capture a greater share of value. Yet moving beyond semi-processing into globally competitive chocolate production faces significant hurdles, many of which are deeply structural.

The first obstacle lies in the cost of energy and inputs. Chocolate manufacturing is energy-intensive, and high or unstable electricity prices in many African countries drive up production costs. Beyond energy, essential inputs such as sugar, powdered milk, and food-grade packaging often have to be imported, adding both expense and logistical complexity.

Technology and expertise present another barrier. Producing high-quality chocolate requires advanced machinery and refined technical skills—whether mastering flavor profiling, conching, or tempering. Such expertise is not yet widely available locally, and access to cutting-edge equipment and training remains limited.

Even when production is possible, stringent quality and food safety standards add another layer of difficulty. Competing globally demands rigorous quality control systems and internationally recognized certifications, both of which are costly and complicated to implement.

Then comes the challenge of marketing and distribution. The global chocolate market is dominated by entrenched multinationals with vast budgets and global retail networks. African brands struggle to gain visibility, build recognition, and secure access to supermarket shelves or specialty stores abroad. Financing is also a persistent bottleneck: large-scale chocolate processing requires heavy upfront investment, but African entrepreneurs often face limited access to affordable, long-term credit.

Finally, there is the question of consumer perception. For decades, chocolate has been synonymous with Europe or North America, and the idea that African chocolate is somehow of lower quality—however unfounded—still lingers. Overcoming this bias requires sustained branding, storytelling, and consumer education to promote the quality and authenticity of African-origin chocolate.

By-Product Valorization as a Bridge

Given these realities, it may be more pragmatic not to focus exclusively on producing finished chocolate but to diversify value-addition strategies. Valorizing cocoa by-products offers a promising bridge. The mucilage can be transformed into juice or vinegar, non-deodorized cocoa butter can feed cosmetics, and husks can be turned into bioplastics or fertilizers. These pathways are far less capital- and technology-intensive than chocolate manufacturing, yet they can generate substantial revenues.

Crucially, they can be pursued locally, creating jobs, developing skills, and enabling African businesses to gain experience with transformation processes, quality standards, and international market dynamics. Over time, these alternative value chains can serve as stepping stones, allowing cocoa-producing countries to build expertise, accumulate capital, and gradually develop their own strong brands.

Our podcast “Autour du Cacao” highlights precisely such initiatives, showcasing entrepreneurs who are reimagining cocoa beyond the bean. Their work demonstrates that the future of Africa’s cocoa sector need not be a binary choice between exporting raw beans and competing head-on with chocolate giants. By fully valorizing the fruit in all its forms, Africa can carve a distinctive, resilient, and ultimately more profitable place in the global cocoa economy.

Farmer Economics

Cocoa farmers remain trapped in poverty despite feeding a $130+ billion chocolate industry. Beyond pricing mechanisms like the Living Income Differential, what structural solutions could transform farmer livelihoods?

That cocoa farmers remain trapped in poverty while fueling a chocolate industry worth over $130 billion is a glaring injustice. Mechanisms like the Living Income Differential (LID) are steps in the right direction, but they remain stopgap measures. To truly transform farmer livelihoods, structural solutions must target the root causes of poverty.

The first imperative is diversification. Dependence on cocoa alone leaves farmers at the mercy of volatile markets and climate shocks. Integrating food crops, alternative cash crops, or even livestock into farming systems can stabilize incomes and enhance household food security. Agroforestry is particularly promising, allowing cocoa to be cultivated under the shade of fruit and forest trees that generate additional income streams while improving ecological resilience.

Equally critical is the valorization of cocoa by-products. The fruit is more than just the bean: mucilage, husk, and pulp all carry economic potential. Small-scale transformation into juices, vinegar, biochar, or animal feed can unlock new revenue sources that were previously wasted. But realizing this potential requires targeted training in processing techniques and the creation of viable market linkages for these new products.

Finance is another missing piece. Too often, farmers remain excluded from formal financial systems, with little access to credit, insurance, or savings tools. Expanding access to tailored microfinance, climate-risk insurance, and savings schemes would empower farmers to invest in productivity improvements, weather lean seasons, and withstand unexpected shocks.

Collective organization also matters. Strong cooperatives and producer associations can shift the balance of power in farmers’ favor. By pooling resources, they can negotiate better input prices, organize collective marketing, and share services such as training or equipment. This reduces dependence on intermediaries and ensures that more value remains in farmer hands.

Training and technology transfer are essential complements. Practical instruction in good agricultural practices, post-harvest handling, and quality improvement can directly raise yields and incomes. At the same time, capacity building in by-product processing equips farmers to diversify income streams in more innovative ways.

Finally, rural infrastructure must not be overlooked. Roads, energy, and water systems may seem distant from farm-level economics, but they are in fact central. Better infrastructure reduces transport and transaction costs, improves access to inputs and markets, and makes it easier for farmers to connect with financial and extension services.

In short, lifting cocoa farmers out of poverty requires moving beyond short-term pricing fixes. Only by diversifying farm economies, valorizing the full potential of cocoa, expanding financial inclusion, strengthening collective power, and investing in rural infrastructure can the industry close the gap between a multibillion-dollar chocolate market and the smallholders who sustain it.

Consumer Shifts in Europe

How are European trends—demand for dark chocolate, sugar reduction, ethical sourcing—reshaping the cocoa value chain, and where can African producers plug into these shifts?

Consumer trends in Europe—particularly the appetite for dark chocolate, the push for sugar reduction, and the insistence on ethical sourcing—are not passing fads. They are rewiring the cocoa value chain and, crucially, creating new entry points for African producers willing to adapt.

The growing demand for dark chocolate is the clearest signal. By emphasizing the intrinsic quality of cocoa and its complex flavor profiles rather than sugar or additives, European consumers are rewarding producers who can deliver beans with distinctive aromas and terroir. For African farmers, this makes investment in fermentation and drying techniques far more than a technical upgrade—it is a passport to direct partnerships with artisan chocolatiers and niche brands that prize origin-specific identity.

Sugar reduction amplifies this trend. As consumers gravitate toward richer flavors less masked by sweetness, the aromatic depth of cocoa comes into sharper focus. African beans, with their varied profiles, are well positioned to serve as the backbone of low-sugar chocolates that still feel indulgent. This shift also opens the door to innovation in cocoa-based products that aren’t necessarily confections at all—pure cocoa beverages, extracts, and functional ingredients that lean on authenticity rather than added sugar.

The most powerful driver, however, is ethical and sustainable sourcing. European buyers are scrutinizing the origins of cocoa like never before, linking their choices to farmer livelihoods, environmental impact, and traceability. With the EU Deforestation Regulation now transforming ethical sourcing from a consumer preference into a legal requirement, the message is unambiguous: cocoa that cannot prove it is deforestation-free and responsibly grown will struggle to enter the European market. For African producers, this presents both a challenge and an unprecedented opportunity to differentiate through certifications, agroforestry practices, and fair labor commitments.

Seizing this moment requires a multi-pronged strategy. Producers must first shift from bulk cocoa to specialty-grade beans, focusing on quality and differentiation. Building robust traceability systems—complete with parcel geolocation and transparent documentation of farming practices—will be non-negotiable to satisfy both regulators and consumers. Beyond the bean, there lies another frontier: valorization of by-products. Europe’s interest in natural, functional, and sustainable ingredients is growing, and cocoa mucilage, husk, and pulp can be transformed into beverages, cosmetics, and nutraceuticals that speak directly to sugar-conscious, health-oriented consumers. Cocoa juice, rich in antioxidants, is already a candidate for positioning as a healthy, natural drink aligned with Europe’s low-sugar ethos.

But meeting these trends is not just about production; it is about narrative. European consumers increasingly want to know the story behind their chocolate—its terroir, its communities, its sustainable practices.

Finally, success will require forging strategic partnerships. By aligning with European companies committed to sustainability and innovation, African producers can not only gain access to markets but also benefit from technology transfer, co-branding opportunities, and new product development. In doing so, they cease to be mere suppliers of raw material and instead emerge as co-creators of the future of chocolate.

In short, Europe’s shifting consumer landscape is more than a compliance challenge. It is a chance for Africa to rewrite its role in the cocoa economy—by doubling down on quality, embedding traceability, valorizing every part of the fruit, and telling its story with conviction.

Africa–Europe Power Balance

Historically, Europe has set the rules and Africa has supplied the beans. Do you see the relationship evolving toward a more balanced partnership, or will structural dependency persist?

Historically, the relationship between Africa and Europe in the cocoa industry has been one of stark imbalance: Europe set the rules while Africa supplied the beans. Today, however, there are signs of this dynamic shifting toward a more balanced partnership—even if the risk of structural dependence remains unless bolder reforms take root.

Signs of Evolution

The first indicator of change lies in Africa’s growing ambition to process more cocoa locally. Every ton transformed into paste, butter, or powder within producing countries represents value captured at origin rather than ceded to European processors. While competing with global chocolate giants remains a long-term challenge, the rise of African chocolatiers and the steady growth of domestic grinding capacity signal a meaningful shift.

Equally transformative is the valorization of by-products. By extracting value from cocoa mucilage, husk, and pulp, African innovators are building entirely new economic sectors that do not directly compete with Europe’s chocolate industry. Products such as cocoa juice, biochar, and cosmetics diversify income streams and reposition Africa not as a raw material supplier but as a source of innovation.

Producer organizations and institutions are also becoming more assertive. Stronger cooperatives, regional blocs such as ECOWAS, and proactive government policies are giving farmers a greater collective voice. At the same time, European consumer demand for ethical, sustainable, and traceable cocoa is granting African producers new leverage. Those who meet these standards can forge more direct, equitable partnerships with buyers and negotiate improved terms. Finally, knowledge and technology transfer partnerships are enabling African actors to climb further up the value chain, from farming to processing to marketing.

Risks of Persistent Dependence

Yet these advances could stall if structural barriers are not dismantled. Without large-scale investment in infrastructure, energy access, and training, local processing ambitions risk falling short. International regulations, such as the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), may also entrench inequality if imposed as compliance burdens without financial or technical support. Unless producing countries coordinate their approaches to European buyers, fragmented strategies will continue to weaken bargaining power.

Outlook

In short, the balance is shifting but not guaranteed. Africa’s determination to capture more value, combined with European consumers’ ethical expectations, is laying the groundwork for a new kind of partnership. To consolidate this progress, however, investment, supportive policy frameworks, and cross-border collaboration remain essential. The future of cocoa depends on whether the industry can finally transcend its colonial inheritance and build a relationship defined by shared value rather than structural dependency.

Role of Policy and Institutions

How effective are current interventions by African governments, regional blocs, and industry alliances in shifting bargaining power? What policy gaps still hold Africa back?

The interventions of African governments, regional blocs, and industry alliances are increasingly important in rebalancing negotiating power in the cocoa sector. Yet their effectiveness is uneven, and persistent policy gaps continue to limit Africa’s ability to fully capture value.

Effectiveness of Current Interventions

National governments have made strides by encouraging local processing through tax incentives and industrial free zones, improving cocoa quality through certification programs and research centers, and supporting farmers with subsidies or guaranteed prices. Regulatory bodies such as Côte d’Ivoire’s Coffee-Cocoa Council and the Ghana Cocoa Board have brought greater organization and a measure of protection to farmers.

Regional blocs such as ECOWAS and ECCAS hold potential to integrate regional cocoa markets, harmonize policies, and strengthen Africa’s collective bargaining power with international buyers. Their industrialization and diversification initiatives mark steps in that direction, though they remain works in progress.

Industry alliances, notably the Cocoa & Forests Initiative (CFI), have mobilized resources to address deforestation, child labor, and traceability. These programs help align African producers with evolving European sustainability requirements and build credibility in global markets.

Persistent Policy Gaps

Despite these advances, several gaps blunt the impact of interventions. A lack of coordination—between ministries and among producing countries—often dilutes the effectiveness of national and regional policies. The broader business environment also poses challenges: corruption, bureaucracy, and political instability discourage both local entrepreneurship and foreign investment.

Access to long-term, affordable finance remains another weak link. Without credit, insurance, and investment capital, smallholder cooperatives and SMEs struggle to scale processing, adopt innovation, or valorize by-products. Research and development is underfunded, with too few centers of excellence or public–private partnerships driving new varieties, farming practices, or product innovation.

Infrastructure deficits—from unreliable energy and poor roads to limited storage—continue to raise costs and erode competitiveness. Finally, policy frameworks rarely extend to by-product valorization. The absence of clear standards and incentives has slowed the commercialization of products like cocoa juice, biochar, or husk-based materials that could open entirely new markets.

The Way Forward

For Africa to move beyond bean dependency, policies must become more integrated, coordinated, and backed by substantial investment. Governments need to create an environment conducive to entrepreneurship, innovation, and sustainable value capture across the entire chain—not just at the farm gate. Closing these gaps is the only way to convert current efforts into real bargaining power and position Africa as an equal partner in the global cocoa economy.

The Next Decade

By 2035, what does a successful African cocoa economy look like in your view? And conversely, what risks could derail progress if current dynamics don’t change?

By 2035, a successful African cocoa economy would look radically different from today’s. The continent would no longer be confined to exporting raw beans but would command a diversified, integrated value chain. A significant share of cocoa would be processed locally—not only into paste, butter, and powder, but also into high-quality chocolates sold under internationally recognized African brands. Just as importantly, by-products once discarded would fuel thriving new industries. Companies would be producing cocoa juice, vinegar, cosmetics, bioplastics, organic fertilizers, and even pharmaceutical ingredients, creating new revenue streams and jobs.

Farmers themselves would be prosperous and autonomous. Living incomes would be secured through fairer bean prices, diversified earnings from agroforestry and by-product valorization, and far better access to finance and services. Farmers would operate as skilled entrepreneurs, organized into powerful cooperatives that negotiate directly with buyers.

Agriculture would also be sustainable by default. Regenerative practices and agroforestry would enhance soils, protect biodiversity, and build climate resilience, while deforestation linked to cocoa would be eliminated through traceable, forest-positive production systems.

African leadership would be more visible and more coherent. Governments and regional blocs would back industrialization with consistent policies, R&D investments, and market-access strategies. On the global stage, Africa would speak with one voice, asserting the interests of its producers and processors.

Perhaps most importantly, a new generation would see agriculture as a sector of opportunity, not last resort. Through innovation, entrepreneurship, and social recognition, farming would attract youth, with initiatives such as Kids Farming inspiring children to view sustainable agriculture as both purposeful and aspirational.

Risks of Derailment

But this vision is far from guaranteed. If investments in local processing and by-product valorization stall, Africa could remain stuck as a raw bean supplier, vulnerable to price swings. Failure to support smallholders in complying with new rules like the EUDR could shut farmers out of European markets, deepening poverty and instability. Climate change poses another existential risk: without widespread adoption of resilient farming systems, yields could collapse under droughts, floods, or disease.

Equally worrying is the financing gap. Without affordable, long-term investment in infrastructure, innovation, and SMEs, ambitions may wither on paper.

The Imperative

The next decade will be decisive. Turning Africa’s cocoa economy into a diversified, sustainable, and youth-driven powerhouse requires collective, coordinated action across governments, industry, and civil society. Innovation, diversification, and empowerment of local actors must move from rhetoric to reality. The future of cocoa is in Africa—but only if Africa seizes it on its own terms.

—- Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)