Saturday, 21 February 2026

Image Source: Yarafert

The ever-evolving chessboard of Asian geopolitics is witnessing China’s quiet throttling of specialty fertilizer exports thereby casting a long shadow over India’s precision agriculture ambitions. As high-value crops brace for nutrient shortfalls ahead of the Rabi season, India’s agri-value chain finds itself perilously exposed to the vagaries of trade dependence and supply disruptions. The crisis has not only unmasked the fragility of India’s import-heavy fertilizer ecosystem but has also ignited urgent calls for a domestic renaissance in nutrient innovation and manufacturing. Stakeholders across industry, research, and policy now converge on the imperative to build a future-ready, soil-centric model rooted in resilience, customization, and scientific stewardship. While stopgap measures scramble to plug short-term voids, the deeper opportunity lies in catalyzing India’s emergence as a self-reliant powerhouse in next-generation agri-inputs. The fertiliser faultline, once a geopolitical tremor, may well become the crucible in which India redefines its $1 trillion agri dream.

In the swirling eddies of global trade, few relationships are as complex—and as consequential—as that between India and China. These two Asian behemoths, home to nearly 3 billion people combined, have walked diverging yet strangely parallel economic paths. Today, both countries stand tall in the global economy, yet their trade relationship tilts sharply.

Specialty fertilizers are now central to modern farming—boosting yields, improving nutrient efficiency, and cutting environmental impact through precision delivery. However, India’s heavy reliance on China, which once supplied 80 per cent of its specialty fertilizer needs, has turned into a strategic risk. Over the past few years, China has quietly throttled exports—delaying inspections and stalling shipments. Today, those exports have nearly ceased, not by decree but by design. As supply chains seize up, India’s agri-value chain is left scrambling for alternatives.

“The disruption in specialty fertilizer supply couldn’t have come at a worse time,” said Dr. Kaushik Banerjee, Director, ICAR–NRCG. “With the Rabi season approaching, high-value crops like grapes, tomatoes, flowers, and potatoes—already under pressure from climatic stress—face a dual blow. Without timely and targeted nutrition, both yield and quality are at stake. This is not just a supply issue; it’s a farm income crisis in the making. The need for swift, strategic policy action is urgent.”

In a time of geopolitical hardening, it may be the soil—quiet, enduring, and generous—that reminds these giants of what they can still grow together and perhaps, rewrite the global trade playbook.

Feeding fields, fuelling tensions: Inside the China-India fertiliser equation

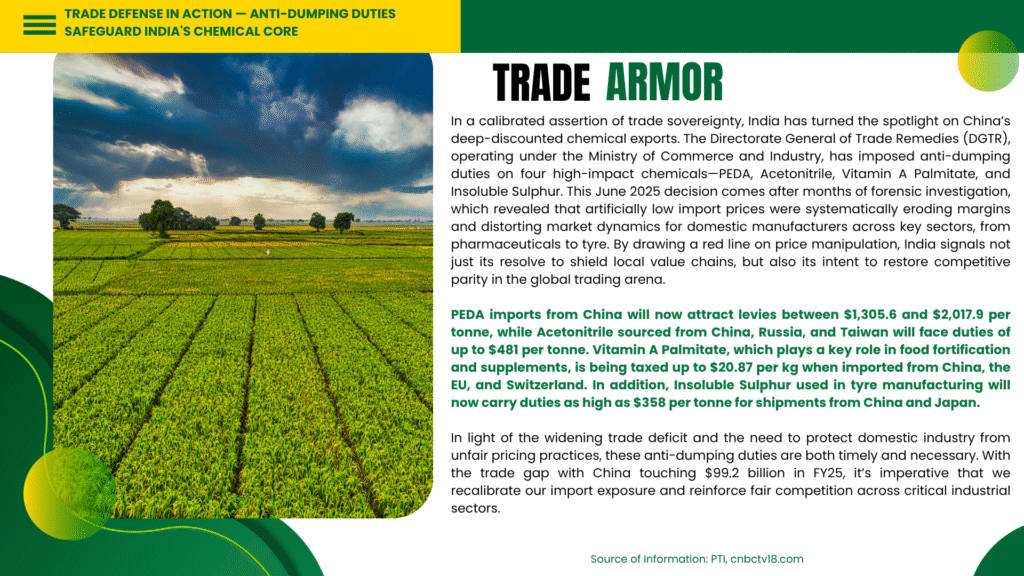

India’s deepening trade imbalance with China—reaching a record $99.2 billion in FY 2024–25—has laid bare critical vulnerabilities in the country’s agri-input ecosystem, especially in the domain of specialty fertilizers. Exports to China fell 14.5 per cent to $14.25 billion, while imports surged 11.5 per cent to $113.45 billion, underscoring India’s persistent dependence on Chinese industrial inputs.

“ Government policies like Make in India and setting up chemical parks are crucial in making the agrochemicals industry of India more export competitive. The schemes drive local manufacturing, reduce dependence on imports, and encourage investment in infrastructure and technology. Chemical parks offer integrated facilities, better logistics, and common utilities, all resulting in lower production costs while conforming to the environment. Furthermore, rapid clearance schemes and ease of product registrations in focus markets also enhance market access “.

—– M K Dhanuka, Chairman, Dhanuka Agritech Ltd

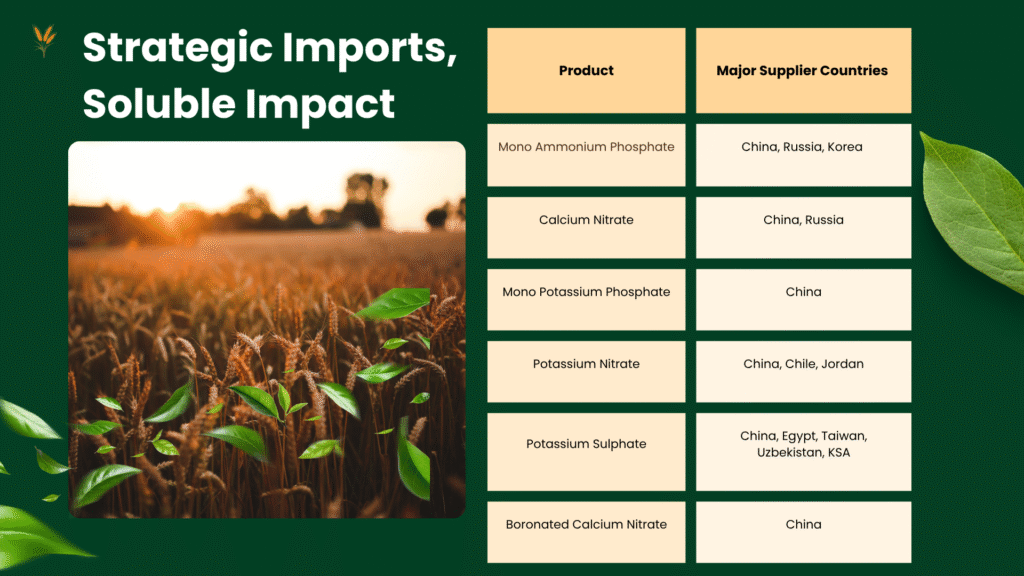

While New Delhi has made progress in diversifying sources for bulk fertilizers like urea and DAP, its specialty fertilizer portfolio—comprising water-soluble fertilizers (WSFs), micronutrients, nano formulations, and biostimulants—remains disproportionately reliant on China. These high-efficiency inputs have become the backbone of India’s precision agriculture, vital for fertigation-based cultivation of high-value crops such as pomegranates, grapes, chillies, and floriculture products.

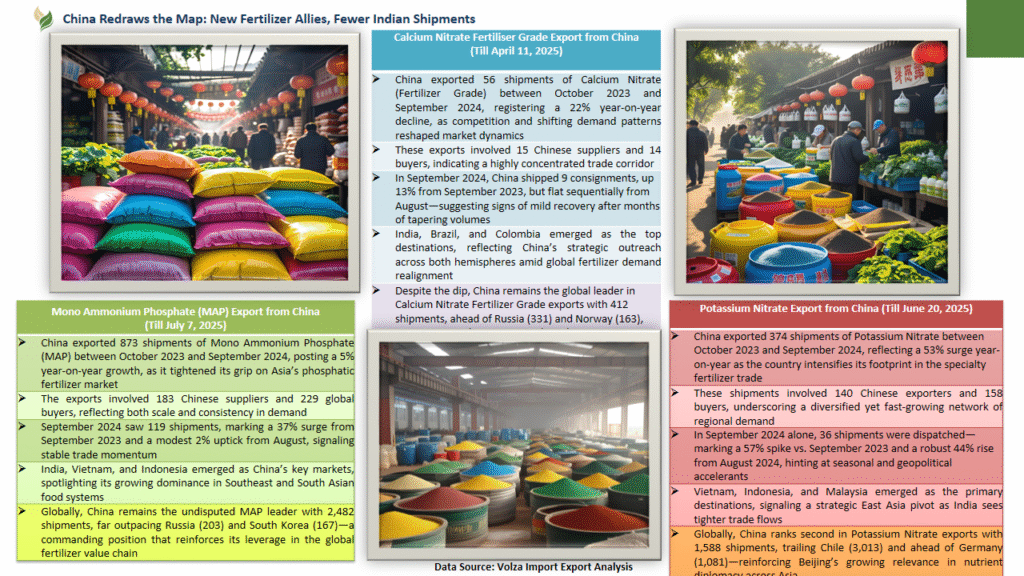

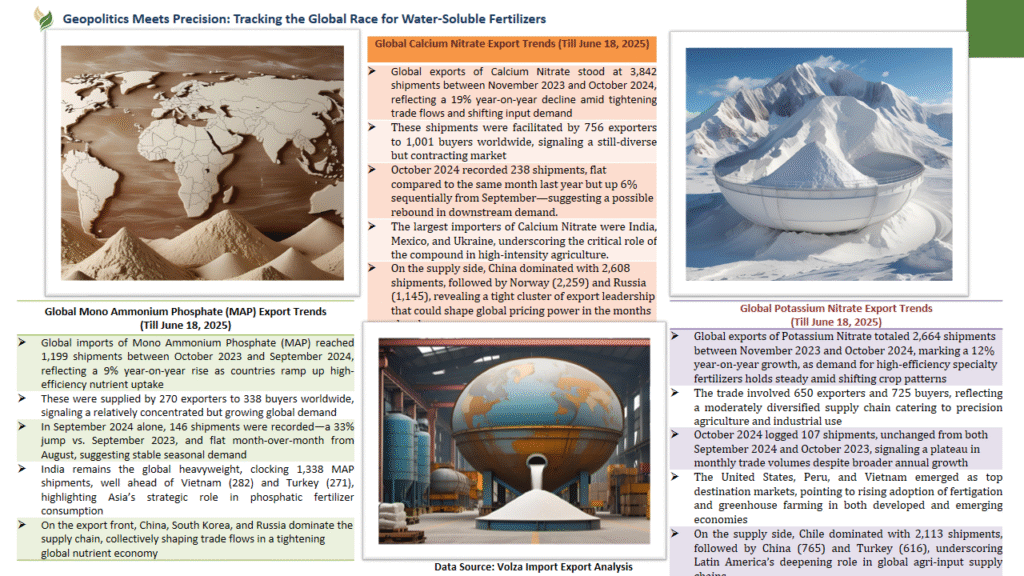

According to Volza import data, India imported 24,969 shipments of WSFs between October 2023 and September 2024, involving 475 exporters and 341 Indian buyers. The pace of imports remains robust, with 429 shipments in September 2024 alone, signalling a structural demand shift. However, the sourcing concentration is stark: China still accounts for over 60 per cent of WSF volumes, with key products like Mono Ammonium Phosphate (MAP), Calcium Nitrate, and Magnesium Sulphate overwhelmingly routed through major Chinese ports.

Alarmingly, the three principal ports—Chongqing, Qinzhou, and Yichang—are witnessing a rapid contraction in outbound fertilizer shipments. From 2023 to 2025, Chongqing’s exports to India halved from 1,200 Mt to 600 Mt, Qinzhou declined from 1,000 Mt to 400 Mt, and Yichang fell from 800 Mt to just 300 Mt. These port-level slumps are not incidental; they reflect a calibrated export slowdown driven by China’s internal policy pivot toward domestic food security and resource prioritisation.

“India stands on the brink of an agronomic transformation—where the fusion of precision agriculture, eco-conscious inputs, and enlightened policy can catalyse a new era of farm productivity. As the global speciality fertiliser market races toward $63 billion by 2035, India’s own segment is projected to surge to $6 billion by 2030, growing at 18 per cent annually. This is our moment to sow sustainability and reap strategic self-reliance “

—- Dr Kaushik Banerjee, ARS, FNAAS, Director, ICAR–NRCG

India is already feeling the tremors. The DAP crisis, once a periodic concern, has escalated into a systemic threat—import prices surged to $810 per tonne in mid-2025, while opening stock levels fell to 900,000 tonnes as of June 1, 2025, marking a steep 42 per cent drop from 1.56 million tonnes a year earlier. With Vietnam emerging as the world’s top WSF importer (clocking 35,856 shipments), and Ukraine closely following (18,930 shipments), India finds itself both geopolitically and competitively squeezed.

“Fertilisers remain one of the most expensive and import-dependent inputs, with a substantial subsidy burden on the national budget. Therefore, their application must be guided by best management practices, particularly the 4R Nutrient Stewardship framework—Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, and Right Place. Specialty fertilisers are central to this strategy and must be integrated more fully into India’s nutrient management policies “

— Jayanta Chakraborty, Chairperson, Agri-Horti-Food Processing & Rural Development National Committee, BCC&I

This fragmented, import-heavy model is increasingly untenable. Without decisive investment in domestic manufacturing clusters, public-private R&D pipelines, and logistics infrastructure to support local formulation and blending, India risks ceding control over its agricultural future to volatile global markets and foreign policy calculus.

Suggesting counter strategy in hours of crisis, M K Dhanuka, Chairman, Dhanuka Agritech Ltd highlighted regions like Latin America, Southeast Asia, and Africa as emerging as high-growth markets for Indian agrochemical exports. “Countries such as Brazil, Vietnam, and Japan are witnessing intensified farming activity—driving demand for cost-effective, efficient crop protection solutions. Indian firms are responding with agility: securing product approvals, reformulating for region-specific crops, strengthening distribution networks, and aligning with international sustainability and compliance standards,’’ he mentioned.

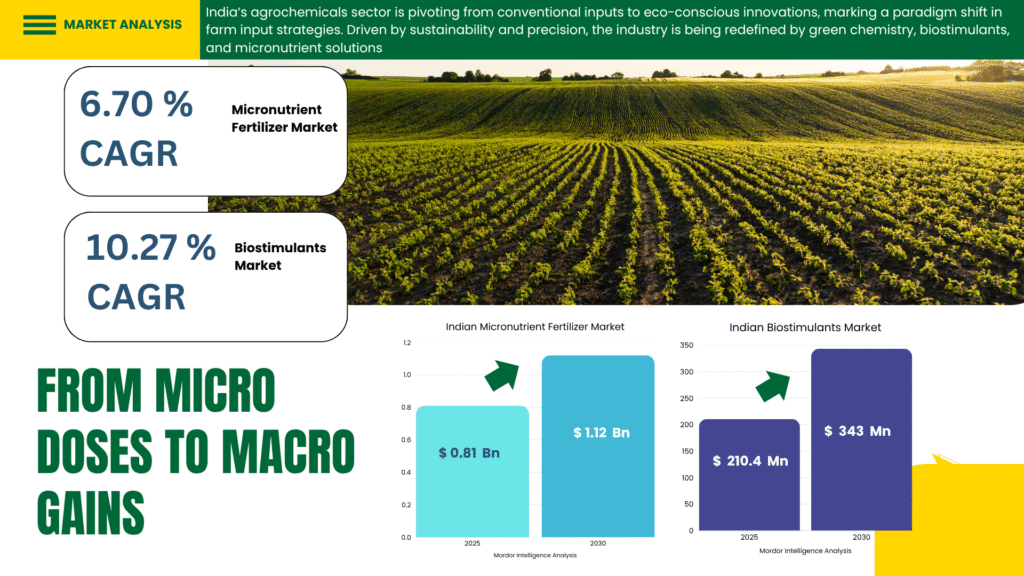

India’s agri-input landscape is rapidly evolving, with specialty segments like micronutrient fertilisers and biostimulants gaining significant traction. The India Micronutrient Fertiliser Market, currently valued at $810 million, is projected to reach $1.12 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 6.7 per cent. Even more dynamic is the India Biostimulants Market, expected to surge from $210.4 million in 2025 to $343 million by 2030, at a robust CAGR of 10.27 per cent. These growth trajectories underscore a shift toward high-efficiency, sustainable farming practices—driven by precision agriculture, export-oriented horticulture, and increasing regulatory focus on soil health. As India scales up its agri-value chain, these inputs are no longer niche—they’re foundational.

“China’s opaque policy stance may have disrupted the supply of specialty fertilisers, but in that disruption lies a silver lining. By pulling back, China is inadvertently creating space for emerging economies like India to establish their own production ecosystems “

—- Rajib Chakraborty, National President, SFIA

When inputs stall, exports fall: The Domino Effect of a supply disruption

China’s suspension of specialty fertiliser exports to India hasn’t sparked a shortage—yet. However, the damage is already done: Prices are rising globally, and India’s dependence on a strategic rival has been laid bare. Most Indian fertiliser companies remain buffered by their focus on bulk nutrients like urea and phosphates, but the real risk lies in specialty inputs—micronutrients, nano formulations, water-soluble blends—that drive precision farming and future yield. With China continuing shipments elsewhere while selectively stalling India’s, the message is clear: this is calculated economic pressure, not coincidence.

Yet the disruption stretches far beyond the farm gate. Input manufacturers dependent on Chinese raw materials are running down inventories at an alarming rate.

” Today, bio- and nano-formulation approvals can stretch over years—without a fast-track regime akin to pharma or electronics. The irony is profound: While we digitise nutrient delivery through PM-PRANAM and DBT, the innovation pipeline remains stuck in analog red tape. If Atmanirbhar-Bharat is to become strategy—not restricted to a mere slogan—it must begin by reforming the ecosystem that governs agri-input innovation. The time is ripe for India to articulate a “Fertiliser Sovereignty” doctrine. This does not imply autarky, but rather strategic autonomy: the ability to absorb external shocks without cascading impacts on farm productivity or fiscal stability ‘’

—— Dr. Pranjib K Chakrabarty, ARS, FNAAS, Former Member ASRB, Govt of India & Assistant Director General (Plant Protection & Biosafety), ICAR, DARE, Ministry of Agriculture

The halt poses serious short-term challenges for Indian farmers. Without timely access to these inputs, the productivity and profitability of the upcoming agricultural cycle may be compromised. While Indian firms are positioned to ramp up local production, a lack of sufficient infrastructure and technology readiness means that domestic manufacturing cannot yet fill the gap. In response, the Indian government and private sector players are exploring alternative import sources, including countries like Jordan and several European nations. However, logistics, pricing and quality assurance remain hurdles in establishing new supply routes quickly.

Even minor deviations in nutrient protocols can lead to shipment rejections, reduced premiums, or loss of market access. Traceability systems like GrapeNet and Hortinet—which anchor India’s credibility in the fresh produce trade—leave virtually no room for error. At the same time, logistics chains are buckling under pressure, with stuck consignments, uncertain sourcing timelines, and minimal buffer stocks to carry the system through the quarter. On the domestic front, Indian manufacturers have ramped up production of select formulations.

“ India’s fertiliser challenge is not just about replacing imports—it’s about reimagining the system from the ground up. While domestic manufacturing must scale, it alone won’t close the gap. What we need is a grassroots innovation surge. Our agri-tech startups—pioneering soil analytics, nutrient mapping, and bio-based solutions—must be backed by targeted subsidies, state-level demand aggregation, and structured incubation “

—- Manohar Malani, Mentor, MitraSena

“China’s opaque policy stance may have disrupted the supply of specialty fertilizers, but in that disruption lies a silver lining. By pulling back, China is inadvertently creating space for emerging economies like India to establish their own production ecosystems “, opined Rajib Chakraborty, National President, SFIA.” While the immediate crisis can be bridged through a mix of alternative sourcing and scaling up domestic manufacturing, the long game demands more. We must aggressively invest in grassroots innovation, onboard state governments, and lay the policy and infrastructure foundations for a resilient ‘Make in India’ strategy. This is not just a response to a supply shock—it’s a generational opportunity to build self-reliance from the soil up,” he advocated.

Industry bodies such as the Fertiliser Association of India (FAI) and Indian Potash Limited (IPL) have urged the government to fast-track approvals for substitute formulations and initiate emergency procurement through diplomatic channels.

“India’s fertilizer challenge is not just about replacing imports—it’s about reimagining the system from the ground up. While domestic manufacturing must scale, it alone won’t close the gap. What we need is a grassroots innovation surge. Our agri-tech startups—pioneering soil analytics, nutrient mapping, and bio-based solutions—must be backed by targeted subsidies, state-level demand aggregation, and structured incubation’’, added Manohar Malani, Mentor, MitraSena. “At the same time, fertilizer PSUs, private players, and co-operatives like IFFCO must converge on a common R&D mission—developing nano-fertilizers, liquid blends, and precision applicators tailored to India’s vast agro-climatic diversity. The future of nutrient security lies in collaboration, customization, and courage to innovate locally,” he added.

Fertiliser Fallout: A Wake-Up Call for India’s $1 Trillion Agri Dream

India’s agricultural ascent cannot rely on traditional inputs alone. As the sector enters a new era—defined by climate volatility, global market integration, and the imperatives of sustainability—the foundation must shift. Precision inputs are no longer a premium add-on; they are the very architecture of future-ready farming.

“The evolving complexity of India’s soil health and crop nutrition demands a strategic pivot in how we manage fertilizers. The inclusion of Customized Fertilizers (CFs) under the Fertilizer Control Order (FCO) was a progressive step, enabling region- and crop-specific solutions through precision and fusion-blend technologies’’, stated Jayanta Chakraborty, Chairperson, Agri-Horti-Food Processing & Rural Development National Committee, BCC&I. ’’ Alongside slow- and controlled-release variants, water-soluble formulations, and micronutrient blends, these specialty fertilizers are central to next-generation nutrient management. Yet, their adoption remains patchy. In a sector weighed down by costly imports and mounting subsidy burdens, embedding these innovations within the 4R Nutrient Stewardship framework—Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, and Right Place—is not just agronomic best practice. It is economic necessity and ecological wisdom,” Chakraborty added.

India’s goal of becoming a $1 trillion agri-economy is not misplaced—but it cannot be pursued on an input base that’s brittle, borrowed, or broken. “In recent weeks, India has once again found itself vulnerable to a recurring Achilles’ heel in its agricultural economy—its dependency on imported high-efficiency inputs. It’s tempting to treat disruptions like this as isolated incidents—mere wrinkles in global trade. However, to do so would be a strategic misstep “, advocated Dr. Pranjib K Chakrabarty, ARS, FNAAS, Former Member ASRB, Govt of India & Assistant Director General (Plant Protection & Biosafety), ICAR, DARE, Ministry of Agriculture.

“From soluble fertilisers and pesticides at n-1, sourced from China, to edible oil from west and Southeast Asia, to pulses from Africa, India’s agri-value chain continues to be shaped by external dependencies that are not just economic vulnerabilities—they are strategic liabilities. India’s Rs 15,000 crore PLI scheme must now shift from privileging legacy scale to empowering frontier innovation. SMEs developing SOMS including soluble fertilisers, organic and microbial blends, biostimulants and climate-smart inputs need not just funding, enabling policies, research but also the speed “, he stated.

The fertiliser squeeze, for all its near-term sting, might just be the jolt the sector needed. Sometimes, crises collapse supply. Other times, they awaken vision. This moment holds the potential to do both.

In words of Dr. Banerjee, “This is a once-in-a-decade opportunity to reimagine India’s fertilizer landscape—not merely as a response to disrupted imports, but as a springboard toward strategic self-sufficiency. If seized with vision and urgency, this moment could mark the shift from reactive substitution to long-term competitiveness—strengthening rural economies, reducing subsidy burdens, and positioning India as a global hub for next-generation nutrient solutions. The crisis may have started at the ports, but its solution begins in our soils.”

——— Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)