Tuesday, 27 January 2026

In 2025, India’s MSP system evolved from a simple safety net into a strategic instrument, subtly reshaping cropping decisions, incentivizing diversification into pulses, oilseeds, and coarse grains, and aligning farmer choices with long-term food security and import-reduction goals

India’s Minimum Support Price (MSP) system has long been a linchpin of agricultural policy, promising farmers a guaranteed price for designated crops and serving as a buffer against market volatility. Yet in 2025, MSP adjustments have evolved beyond their traditional role as a simple safety net. The latest hikes have subtly but meaningfully reshaped cropping decisions, risk perception, and farm economics, signaling a structural shift in Indian agriculture that often goes unnoticed.

MSP Adjustments in 2025: Policy Nuance Over Blunt Hikes

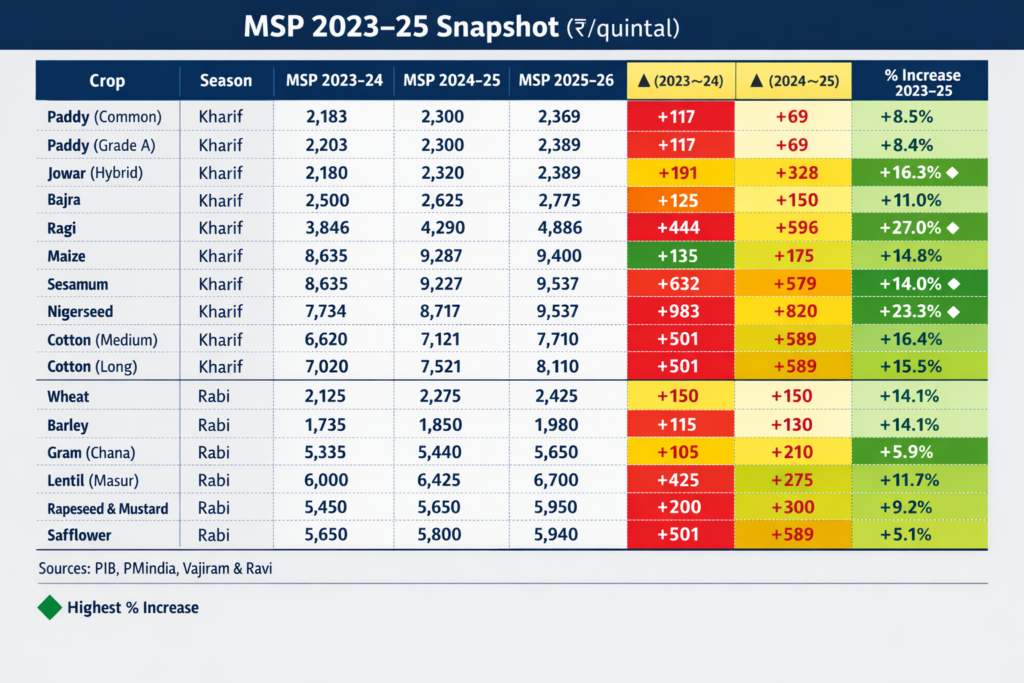

For the 2025–26 marketing season, the Union Cabinet implemented a more nuanced MSP framework, reflecting both fiscal prudence and strategic intent. Kharif crops such as common paddy saw a modest increase to Rs 2,369 per quintal, a rise of just Rs 69 over the previous year, while grade A paddy followed the same trajectory, reaching Rs 2,389 per quintal. By contrast, coarse grains and high-protein crops witnessed substantially higher increments. Jowar (hybrid) surged to Rs 3,699, up Rs 328 from the previous year; ragi climbed to Rs 4,886 per quintal, an impressive Rs 596 increase; bajra rose by Rs 150 to Rs 2,775; maize advanced to Rs 2,400 per quintal, gaining Rs 175.

In oilseeds, sesamum and nigerseed received substantial boosts, with the former rising Rs 579 to Rs 9,846 per quintal and the latter Rs 820 to Rs 9,537, while cotton—both medium and long staple—jumped by Rs 589 to Rs 7,710 and Rs 8,110 per quintal, respectively. These differentiated increases highlight a deliberate policy pivot toward crop diversification and strategic self-reliance, signaling to farmers that staples alone are no longer the sole path to income security.

Rabi crops similarly reflected targeted incentives. Wheat continued its stable role as a staple, reaching Rs 2,425 per quintal, up Rs 150 from 2024–25. Barley advanced to Rs 1,980 (+Rs 130), gram (chana) to Rs 5,650 (+Rs 210), and lentils (masur) to Rs 6,700 (+Rs 275). Rapeseed and mustard gained Rs 300, reaching Rs 5,950 per quintal, while safflower saw a moderate increase to Rs 5,940 (+Rs 140). These selective uplifts demonstrate an explicit policy nudge toward pulses, oilseeds, and coarse grains, complementing staple production while encouraging cropping patterns aligned with national food security and import-reduction objectives.

Over the past decade, MSP payouts have more than tripled, exceeding Rs 3.33 lakh crore in 2025, reflecting not just inflation but deliberate policy decisions to reinforce domestic food security and incentivize strategic cropping choices. This design signals that MSP is increasingly a tool for signaling desired cropping patterns rather than merely providing a floor price.

Shifts in Kharif Cropping Patterns

The differentiated MSP increases are already influencing sowing decisions. In central India, particularly Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra, farmers are responding to higher pulses and oilseeds prices by expanding acreage for soybean and tur. Dryland zones are seeing a resurgence in coarse grains like ragi and bajra, made economically viable through elevated MSPs. In Punjab and Haryana, modest paddy MSP increases, when weighed against rising water costs, are prompting farmers to experiment with maize, cotton, or fodder crops despite a robust procurement system for rice.

Pulses illustrate the broader policy effect vividly. Historically marginalized due to chronic import reliance and volatile pricing, pulses now offer credible, risk-adjusted returns. Tur, moong, and urad are attracting attention from farmers who previously prioritized staples, reflecting a slow but perceptible shift in crop portfolio strategies. Farmers are increasingly balancing market demand signals with policy-driven price incentives, demonstrating sophisticated decision-making that incorporates both profitability and risk management.

Rabi Crops and Strategic Incentives

Rabi crops mirror a strategic recalibration. Wheat remains the backbone of the system, with annual increases maintaining production stability. Yet the larger proportional MSP hikes in lentils, gram, and rapeseed/mustard signal a subtle push for diversification.

Safflower, though less prominent, received incremental support, encouraging cultivation in dryland areas where wheat monoculture is water-intensive and less sustainable. The MSP is increasingly functioning as a market signaling tool, subtly directing farmers toward crops that support broader food security and import-reduction goals.

MSP as Implicit Insurance and Risk Management

Beyond direct incentives, MSP functions as implicit insurance. In weather-sensitive crops like soybean, tur, and rice, the guaranteed price floor mitigates downside risk akin to a put option. This protection has become especially important in 2025, as variable monsoons and rising input costs amplify farm-level uncertainty.

Coupled with crop insurance schemes and digital price information platforms, MSP is enhancing farmers’ capacity to make risk-adjusted planting decisions that blend economic rationality with policy safety nets.

Procurement Realities and Market Linkages

The impact of MSP is not solely determined by announced rates.

Procurement logistics and state-level market infrastructure shape the realized benefits. In several states, delays in paddy procurement and regional price gaps have constrained the protective effect of MSP. Farmers with access to storage, transport, and reliable mandis capture more value, highlighting that institutional and logistical support is critical to translate MSP policy into actual income security.

The Quiet Impact on Cropping Decisions

Field-level evidence from 2025 indicates more nuanced farmer choices than ever before. Central Indian farmers are diversifying into pulses and oilseeds, motivated by both MSP and market demand.

Dryland farmers are sustaining or increasing coarse grain cultivation due to improved MSP returns, while farmers in Punjab and Haryana cautiously explore alternative crops in response to water costs and modest paddy gains. These patterns suggest a growing sophistication in decision-making, integrating policy signals, resource constraints, and market opportunities.

Subtle Shifts with Long-Term Implications

Several highlight the quiet but significant impact of MSP adjustments in 2025.

First, the spread of MSP benefits across multiple crops—rather than concentrating only on rice and wheat—is actively encouraging diversification aligned with national food security objectives.

Second, efficacy is increasingly determined by market access; regions with better connectivity and procurement systems capture more value.

Third, policy discourse is evolving, with active debate among farmer organizations and economists on statutory MSP frameworks and cost-plus guarantees (C2+50 per cent), reflecting a maturing approach to price support.

Finally, strategic alignment of MSP with pulses and oilseeds production underscores its role in reducing import dependence, a priority that often remains overshadowed by focus on staple cereals.

A Structural Realignment in Progress

In 2025, MSP has demonstrated its capacity to shape more than incomes; it is influencing cropping portfolios, risk management, and long-term agricultural strategy. By differentiating support across crops and implicitly linking it to resource availability and market signals, the policy is nudging Indian agriculture toward a more diversified, resilient, and strategically aligned landscape.

While logistical and procurement challenges remain, the quiet realignment toward pulses, oilseeds, and coarse grains represents a shift likely to define the trajectory of Indian farming for years to come.

The 2025 MSP narrative is no longer just about support or subsidy—it is about economic signaling, strategic prioritization, and long-term food security, quietly reshaping the decisions made on millions of farms across the country.

— Suchetana Choudhury (suchetana.choudhuri@agrospectrumindia.com)